21 Oct John Cage’s Intensely Beautiful Love Letters to Merce Cunningham

BY MARIA POPOVA

Composer, writer, artist, and Zen Buddhist John Cage (September 5, 1912–August 12, 1992) pioneered the aesthetics of silence, but he was animated by a clamorous inner life. When he was twenty-two, while dating another young man, Cage met artist Xenia Kashevaroff — the Alaskan-born daughter of a Russian priest. He fell instantly in love — perhaps with Xenia herself, perhaps with the promise of life that conformed to social convention and appeased his inner conflictedness about his orientation, perhaps with some combination of the two. They were married in the spring of 1935. But as Cage continued to discover his voice creatively, he had no choice but to make room for his whole self. By the early 1940s, the couple had begun to grow apart and their marriage soon ended in divorce.

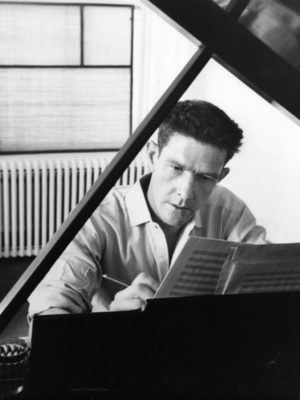

John Cage age his piano, 1947 (Photograph courtesy of the John Cage Trust / Berliner Festspiele)

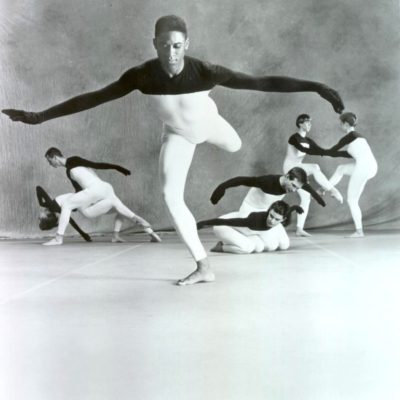

It was around the same time that Cage met the dance prodigy Merce Cunningham, who would go on to become one of the most innovative and influential choreographers of all time. Then in his early twenties, Cunningham was one of several choreographers with whom Cage had begun working in his quest to explore the physical dimension of sound. Although their relationship began as a creative collaboration, a vitalizing romantic electricity developed between them as they got to know each other. Cunningham became Cage’s great love and remained his spouse for the remainder of the composer’s life.

The correspondence from the dawn of their uncommon and intensely beautiful romance, found in The Selected Letters of John Cage (public library), is on par with Nabokov’s love letters — that gold standard of this most intimate genre of the written word — and makes a crowning addition to history’s greatest LGBT love letters.

John Cage and Merce Cunningham at Black Mountain College, 1948 (Photograph courtesy of the John Cage Trust)

In their first surviving romantic correspondence, postmarked June 28, 1943, Cage writes:

Dear Merce,

Saturday night nearly went crazy, because, not solving my problems until they occur, I ever suddenly realized you were gone. Fly away with you but was in a zoo.

[…]

I don’t know when it was that I found out how to let this month go by without continual sentimental pain. It’s very simple now, because I’m looking forward to seeing you again rather than backward to having seen you recently. That’s a happy way to be.

In a sublime testament to the interplay of frustration and satisfaction in love, Cage adds:

I’m unsentimental but I’m sitting at one of our tables and looking in a mirror where you often were.

[…]

I don’t know: this gravity elastic feeling to let go and fall together with you is one thing, but it is better to live exactly where you are with as many permanent emotions in you as you can muster. Talking to myself.

Your spirit is with me.

The following day, Cage writes:

Rain finally came + it’s beautifully cool. Wonder how long it will last. It was marvelous because it started suddenly and then was alternately terrific and gentle.

I think of you all the time and therefor have little to say that would not embarrass you, for instance my first feeling about the rain was that it was like you.

[…]

Love you.

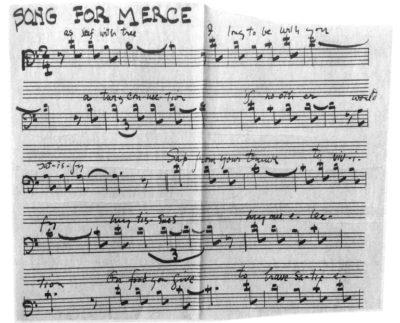

In this letter, Cage encloses a poem he has written for his new love:

POEM. CAUSE: I LOVE YOU.

As leaf with tree, I long to be

With you. A twig connection

If no other, would satisfy.Sap from your trunk to vivify

My tissues; my one election:

On food you give to have satiety.Will leaf turn dry and dead? My

Deep need to pale affection

Fade? Will snail transform to tree?If leaf dies, Spring will mystify

The Winter. No death for tree:

Leaf adorned, ’twill live in ev’ry

section.

Three days later, on July 2, Cage writes from the pit of longing:

I get terribly lonesome for you.

[…]

I nearly left this earth a few minutes ago — ecstasy — word from you. Pretty soon I’ll write music for you.

Scene from Beach Birds by Cunningham at the Lyon Opera Ballet, with music by Cage (Photograph: Michael O’Neill)

Later that month, while Cunningham was in residence with the Martha Graham Dance Company at Bennington College in Vermont, Cage beseeches from New York with affectionate impatience:

Please be lonesome enough to come back in not too distant time.

[…]

I love you and often think of fancy reasons why: spirit is very close to me and mine, I sent it, close to you.

[…]

My whole desire is to run up and down the sea coast looking for you.

Love

Over the year that followed, their love only intensified. In a particularly poetic and picturesque letter from July of 1944, Cage writes:

your letters i just plain love: they bring you so close that at any moment i expect the door will open and you will see me camouflaged in enigmatic home, built on shoes you made.

[…]

Country was beautiful, and lying on the grass so that i could sometimes see the net a tree is against the sky or turning make a space for eyes between two trees and watch bird-movements across and in it. Beautiful daisies and a jungle of tiger lilies. Multitudinous lakes and canoes. I could tell how distinctly happy you would be in country wherever; and i really need not be with you for me or for you, because there was facility in inventing your presence and knowing that just then you were merely not visible or not audible.

Nine days later, Cage writes:

your last letter is so beautiful i cannot answer it, only read it and lie on it.

[…]

i am often in deep pain; i am afraid i am not human being

i talk to you all day long but when i start to write i cannot

Later that month, many decades after Van Gogh articulated how love catalyzes creative work, Cage speaks to this all-consuming muse:

today is beautiful and i am dreaming of you and enigma and how we are together today: your words in my ears making [me] limp and taut by turns with delight. oh, i am sure we could use each other today.

i like to believe that you are writing my music now: god knows i’m not doing it, because it simply seems to happen. the pretissimo is incredible the way you are and is perhaps a description and song about you.

[…]

pardon the intrusion: but when in september will you be back? i would like to measure my breath in relation to the air between us.

Cage and Cunningham continued to fill the air between them with love until the composer’s final breath.

John Cage and Merce Cunningham, 1986 (Photograph: Jack Mitchell / Getty Images)

The Selected Letters of John Cage, edited by Bard College professor and John Cage Trust director Laura Kuhn, is a beautiful read in its hefty totality. Complement it with Cage on human nature and Kay Larson’s sublime cartography of his interior life, then revisit the love letters of John Keats, Hannah Arendt, James Joyce, Iris Murdoch, Vladimir Nabokov, Margaret Mead, Charlotte Brontë, Oscar Wilde, Ludwig van Beethoven, James Thurber, Albert Einstein, Franz Kafka, and Frida Kahlo.