13 Sep PUBLIC THINKER: JACK HALBERSTAM ON WILDNESS, ANARCHY, AND GROWING UP PUNK

BY

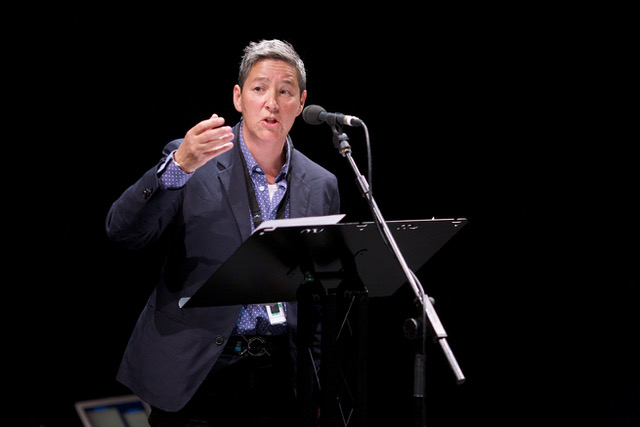

Jack Halberstam is a professor of English and gender studies at Columbia University and the author of six books, including Female Masculinity (1998), In a Queer Time and Place (2005), The Queer Art of Failure (2011), Gaga Feminism: Sex, Gender and the End of Normal (2012), and Trans* (2017). Few authors have been as influential in queer studies; each book has introduced key concepts that have shifted the direction of debates both within and outside the academy. Defying disciplinary categorization, Halberstam’s work draws on legacies of Frankfurt School critical theory, Birmingham Cultural Studies, poststructuralist thought, and critical race theory to produce an account of sex and gender as shifting categories of knowledge and power, bound up in modern systems of racialization, coloniality, and economic disparity.

A prolific author and commentator, Halberstam often addresses a wide public. As founding member of the Bully Bloggers “queer art word group” (2009–2018), his posts on trigger warnings, contemporary cinema, the state of queer theory, and contemporary politics have plumbed the space between academic discourse and the public sphere. Halberstam and I conversed in Oakland, California, about his formation via cultural studies, the trigger-warning debates, anarchy, monsters, and his new book in progress, “Wild Things.”

Damon R. Young (DRY): How do you see your orientation as a thinker?

Jack Halberstam (JH): I’m a low theorist. I really believe in low theory, low culture, and, like Jacques Rancière, I do believe in the “intellectual adventure” that lies beyond the “explicative order” and, furthermore, that one must unlearn mastery. For this reason, we should teach multiple archives of thought and cultural production. I like to teach through materials that range from the very difficult to the very silly.

DRY: You take up figures that are sometimes massively popular and not necessarily avant-garde; well, maybe avant-garde but also popular, like Lady Gaga, Grace Jones, Yoko Ono, David Bowie, Prince.

JH: Yes.

DRY: These figures, in your treatment of them, embody ambivalent currents of cultural thought or possibility, often including possibilities for resistant forms of thinking. Gaga, for example, is not just a sheer product of the commodity system but gives expression to a fantasy or ideal of punk or wild feminism. And then you quote figures like SpongeBob SquarePants—

JH: Yes!

DRY: —and films like Dude, Where’s My Car?

JH: Right, because, to quote Lauryn Hill, “Everything is everything.” You can read some of the same cultural forms and themes in Dude, Where’s My Car as in Chris Marker’s La Jetée. They are both interested in the same questions about temporality, nostalgia, boyhood, the irretrievable past, the fact that because we cannot change the past we are doomed to destroy ourselves. But one is in a comedic and nonsensical and infantile vein, and the other is in a deeply serious and memorializing vein. Similarly, you can find absurdity nestled up to profundity in Shakespeare or SpongeBob. At least, for me, what you can do with the high cultural text you can often do with “low” culture, and, sometimes, it’s better for teaching. But, also, just because something is popular doesn’t mean it’s less complicated; I mean, a comedy is incredibly difficult to pull off.

DRY: Right.

JH: It’s very easy to seem serious. It’s very, very difficult to make large groups of people all find something amusing.

DRY: Many of your books theorize thematically, using terms like wildness, anarchy, queer time, queer failure. I see you as a deeply conceptual thinker. You pull these concepts through a range of cultural sites that traverse divisions between high and low, but also cross national boundaries, and don’t respect disciplinary boundaries.

JH: Yes, that’s true.

DRY: Which in some sense is partly a legacy of Birmingham Cultural Studies. Do you think that’s been an influence on you?

JH: Oh, yes, it absolutely was. I came to the US in 1981 after I failed my university entrance exams, you know, A-levels in England. I was a terrible student, and I was, therefore, very open to the reconceptualizations of knowledge and culture that Stuart Hall and Dick Hebdige and Angela McRobbie offered.

DRY: Ha!

JH: I was a punk in the 1970s and very focused on participating fully in that scene and in understanding the refusals and critiques of imperial culture circulating there. I remember very well later on, after I moved to the US, I heard Dick Hebdige speak about his new book Subculture. Having been a punk, I was intrigued, and I went to hear the talk; I could not believe that this was an acceptable academic subject. I grew up with a very different academia than my father, who was a math professor, did. Like other Jewish refugees of his generation, he saw number theory as a refuge from real life. He invested in a very abstract form of knowledge production and did not believe that it had anything to do with politics or the real world. I consciously rejected that version of academia.

So when I went to hear Dick Hebdige speak, I was hooked. I was really hooked. I didn’t know it at the time, because I did not really understand the talk. It wasn’t entirely clear to me, what he was saying about punk. But I loved the way he did not look like an academic. I loved that he had this little punk book. I loved everything about it. And later on, in graduate school, I had a similar experience after going to a talk by Ann Cvetkovich and another one by Hazel Carby. These scholars allowed me to imagine myself as a scholar.

All of that work by Stuart Hall, Dick Hebdige, Raymond Williams was very, very important to me early on. I probably got a bit stuck in that, and I still hadn’t properly adjusted to understanding how race worked in the US, and, so, in a way, I had to get out of that British paradigm to try to grapple with race and class in the US.

DRY: And yet, you are a Victorianist by training; your first book, Skin Shows: Gothic Horror and the Technology of Monsters (1995), is about gothic fiction.

JH: Yes, I loved reading gothic novels and thinking about monsters in graduate school; my advisor, Nancy Armstrong, turned me in that direction, after I declared my commitment to monstrosity as a theme. I was very happy to do that research and that book. But it wasn’t my passion. I always knew I was going to write a book on female masculinity, which I did—I wrote it almost alongside and at the same time as Skin Shows.

DRY: Female Masculinity (1998) had a similarly galvanizing and inspiring effect on me as a young student in Sydney as what you say about Subculture for you! Some of the themes of that early work continue in “Wild Things,” the new manuscript that you are currently finishing, which explores the trope of wildness as it circulates in a range of cultural sites in the 19th and 20th centuries—

JH: Right.

DRY: —with implications for race and sexuality. Can you say a little bit about the idea of wildness, which runs through several of your recent projects? What does it mean for you and where does it come from?

JH: I think I’ve always written about classification in a way—we were just talking about my first book on monstrosities, which was about bodies that defy classification. And then Female Masculinity was about these in-between bodies that we refuse to or simply cannot classify. Think of Stephen Gordon in The Well of Loneliness, a figure who simply cannot find language for herself. I wrote that book about female masculinity precisely to say that there are categories that both exist within the classificatory system and also defy it. In my turn now to wildness, I offer a counter-archive of bodies and modes of being that fall out of the definitional systems produced to describe them.

DRY: In one sense, this book goes back to your 19th-century roots …

JH: Right, it was fun to think about the 19th and early 20th centuries again. In the early parts of the book, I write about odd characters and figures and writers who do not simply fit into the category of gay as we understand it. They are not longing simply for other men or women; many of them are cathected onto wildness itself. So, I have a whole chapter on lonely men and women who are interested in wild birds and birds of prey, which seems like a really weird category, but it suggests that in a society that has subscribed to a kind of mania for classification there will exist another kind of desire for that which cannot be classified, on the one hand—the nebulous, the in-between—but also for wildness, where wildness is both the “other” to civilization and is the unscripted relationship to governance.

DRY: In the book, you say that the concept of wildness contains histories that are both oppressive and liberating.

JH: Yes, because the category of the wild was created by colonial power to describe peoples and places that needed to come under the sway of colonial rule—so, therefore, it isn’t a clean category. Wildness is a racialized term and has taken on meaning in the context of colonialism; so, the question is, can you possibly wipe the taint off it enough to reuse it? If we make the analogy to queerness, and see that queerness was also the byproduct of a classificatory imperative within medical science, and it was deployed as an insult, we can see how a fetishizing term can be redeployed in a new, activist context. Similarly, I think wildness can offer a framework for thinking about the decolonial, the racialized, the colonized, and unscripted forms of eros under a heading that refuses to be simply another identity.

DRY: Right. That idea of what is outside the framework of identity and of the classifications that structure existing power relations is perhaps the major through line in all of your work; it also connects to the term anarchy, which comes up a lot in your more recent work.

JH: Yes, exactly.

DRY: But wildness is also a name for—it conjures up the idea of nature; what’s not civilized, or is not cultural, is the wild. In your book, you are also exploring the idea of the post-natural, and, specifically, the idea that we are post-natural (the subtitle is Queerness After Nature) …

JH: Right.

DRY: So wildness, paradoxically, references both nature and something that’s not nature or after nature—artifice as the new nature, or the new condition of sexuality, at least. I love this idea of post-natural sexuality.

JH: Yeah. Well, lots of modern queer writers set themselves up against nature (like Wilde and Huysmans), recognizing that nature was a secular heuristic for the normal, the marriageable, the domestic.

DRY: I see.

JH: In tracking these responses to the natural and the anti-natural and the post-natural, we seem to move beyond the epistemology of the closet—here I am quite influenced by Pete Coviello’s book Tomorrow’s Parties. As Coviello says, even when you have a paradigm shift such as that described by the closet, it doesn’t mean that everyone is immediately absorbed by it. A paradigm shift takes effect over years, and, in the process of that shift, people become, as he puts it, “untimely”; they remain connected with older, anachronistic models. You can see that in a much more condensed way today, where someone like me might still identify as butch despite the fact that butch is a deeply anachronistic category for younger people who identify as trans. Paradigm shifts in the digital era happen remarkably quickly. Whereas at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, a shift might take decades and might strand all kinds of bodies outside of recognizable classification.

DRY: I see.

JH: In my chapter on falconry in Wild Things, I discuss the writer T. H. White through Helen Macdonald’s brilliant rendering of him in H Is for Hawk. She is fairly confident that he is a closeted gay man, but I am not sure. I mean, he’s not obviously having relationships with men; he’d like to have relationships with boys, but that’s not an option. He’s into flagellation, sadomasochism, and hawks. What kind of desire is that? As Macdonald points out, the words White uses are fairy, fey, and ferox—and this vocabulary offers a very different geometry of desire, one that runs through the ferox and not the closet, through the binary of domestic/wild and not secret/known.

DRY: That’s super interesting, and something I have also been thinking about, what happens after or beyond the epistemology of the closet. I also love the idea in the book that no sexuality is natural; all sexuality is prosthetic. In Skin Shows, the anti-natural and post-natural take the form of the monster, as a figure that exceeds or doesn’t fit into categories. There you talk about meaning “running riot” and about a “vertiginous excess of meaning”—

JH: Oh, right, yeah.

DRY: So, in a way, wildness is right there from the start of your career.

JH: Yes, the monster is a wild figure, isn’t it? It’s precisely the thing that we make, then we condemn, then we disown.

DRY: Let’s talk about some of your blog posts. Blogging has been a way of intervening in the public sphere of intellectual life beyond the academy.

JH: The blog posts cross over—

DRY: —into a public discourse.

JH: Or they did at the time. I’m not sure if I will write more. The trigger-warning piece, “You Are Triggering Me,” was the first piece I wrote on Bully Bloggers that went viral.

DRY: Well, I want to ask what your position is now, looking back on the debates that piece provoked. Your criticism of the culture of trigger warnings is also a critique of a political culture in which the first move is always to claim victimization and injury. The attachment to identity becomes the attachment to injury, as Wendy Brown once put it.

JH: Right, yes.

DRY: You are also calling attention to a certain intolerance for representations that make us uncomfortable as well as for humorous or ironic registers of speech (which your blog posts often themselves deploy).

JH: Well, on the one hand, I am delighted that students and colleagues are setting limits on the kinds of sexist and racist speech and representations that have long circulated in the university, but I am concerned about the moralism that accompanies the call for trigger warnings. My blog piece on the topic drew from the comedy of Monty Python. I drew so much energy from those films, and they gave me an idiom with which to write the post, which was really silly in places, and, in other places, quite serious about saying no to trigger warnings. The first round of responses seemed to find the blog funny and relevant, but as it circulated more widely, the responses changed and became extremely negative and critical, not just of the piece but of me personally. One person, who signed off as a student from Berkeley, warned me that they knew where I lived and could hurt me! I took a very strong stance in that piece, even in the register of humor, and it has come back to bite me a little bit.

DRY: In the stream of online commentary, you responded to (and accepted) some of the criticisms of that piece, but I’m wondering what your thinking is about that confluence of issues now, which also relates to your Boys Don’t Cry blog post, another one that went viral.

JH: I try to teach students to think about some of the positions that they take in relation to a longer historical arc. That’s one thing I’ve learned from this. It is so important, in an era of 24/7 news feeds, to slow down our reactions, and to think carefully about the context out of which any particular text or film, event or political movement emerged. And so, in relationship to Boys Don’t Cry, we have to situate it in those early years of transsexual/transgender activism and in relation to discussions about the merits of urban versus small town living for queer and trans people. I experienced that film so differently than the response it garners in the present that I have had a hard time understanding what students were protesting in the film. You know, I knew the people who were making the film; I knew what they wanted to do; I knew all about the Brandon Teena case. I remembered the activism that was started around it. I remembered how horrifying the murder of Brandon Teena was and how helpless people felt in the face of such violence.

DRY: Yes.

JH: And I remember my own experience of watching the film for the first time. I was actually quite angry myself about the way the film ended and the way that Peirce seemed to pull back from the credible masculinity she had so carefully constructed for Brandon, and so I guess I should be able to identify with some of the negative responses now. But while I had problems with some of the ways that the trans body was represented in Boys Don’t Cry, I still respected the way it told a very difficult story. I especially admired the experimental visual techniques deployed in the film in an attempt to capture the experience of being trans.

And so, when students wanted the film banned, it worried me. It was baffling to me that people would accuse Kim Peirce of being a “transphobic bitch,” and I quote. It made me angry, and it was very much in line with what I had felt that I had predicted in the trigger warning piece, namely that if our approach to representations from the past is a kind of thumbs up–, thumbs down–evaluative method, we may end up destroying past archives of queer representation. Indeed, it seemed as if the very materials that we as queer people have fought to be able to teach—sexually explicit material, pornography, representations of homophobic and transphobic violence—have suddenly and disastrously been deemed inappropriate or unwatchable.

If this continues, it is possible that those experiences represented by the disturbingly violent films from the past—not just Boys but also The Killing of Sister George, Cruising, and other classic texts—will also disappear into the void of a history denied. We have to be able to examine the disturbing aspects of queer life, the violent experiences, homophobia, transphobic violence, and so on. Students seem to resonate with Heather Love’s essays on cleaving to abject histories, but then it is hard to put those ideas into motion when they refuse to look at the abject material available on film.

DRY: Right. In order to analyze representations, we first have to look at them.

JH: Yes, exactly, and we do not want to fall into the old oppositions between negative and positive images. But then again, I thought my piece on Boys Don’t Crywas clearly in favor of expanding the archive of queer life, not prescribing what goes in and what must be expunged. But my piece was eventually quoted by a right-wing journal to trash students. No outcome can be guaranteed when thousands of people read a blog.

DRY: Right, the blog creates these unexpected assemblages or alliances or resonances between political positions that wouldn’t have otherwise been coherent at all—

JH: —that wouldn’t have ever come into contact, but because of the vertiginous cycling that social media allows, a blog post circulates through multiple websites, and then, suddenly, it passes through a Christian-right website and as it is read more widely, the meaning of it changes.

DRY: Yeah, I see. I mean, in a sense that’s true of anything we write, all language—we don’t own it, and, once it is uttered, it is no longer ours. But the particular forms of circulation that characterize online media are part of a new era of what you call, in another recent blog post I like, “vertiginous capital,” marked by the massive polarization of wealth but also by the complication of cultural and political categories. Under these conditions, blogging is dangerous.

JH: Yes, it is. But I will probably keep writing blogs, because academics and intellectuals generally need lots of venues for our work; we need to be able to write beyond the university, if we have any hope of intervening in ongoing dynamic public discussions.

DRY: Along with wildness, you have been writing recently about anarchy. I want to ask, what is the political vision there? Because I know that you’re also someone who is interested in the politics of resistance and how we should orient ourselves in relation to a newly dystopian set of conditions. Is anarchy a real political possibility or a conceptual figure?

JH: I think that anarchy is a critical concept that has recently been revived in relation to our current set of cascading political crises. Because people have a deep distrust of the state at this point and no longer believe that the state will step up to regulate markets or make any attempt to redistribute wealth or combat white supremacy or guarantee health care or education, then we might legitimately ask whether a state-centered political system actually works.

Many theorists have turned recently to anarchy in their work: Fred Moten and Stefano Harney do so in their brilliant manifesto for The Undercommons. Saidiya Hartman uses the concept of anarchy to describe the political rebellions of black girls in the early 20th century, and she introduces the notion of “waywardness” to describe their palpable refusals of criminalization, domestication, and social morality. Some of Tavia Nyong’o’s work on critical fabulation has an anarchist bent, Jayna Brown’s work on women of color in punk and her new work on Black speculative fiction engages anarchy, and Macarena Gómez-Barris’s new work on indigenous activism in the face of extractive capital also looks to queer and feminist anarchism for alternative formulations of the political. And so on.

In a way, the contemporary anarchist does not seek to make life better under the current conditions of exploitation and extraction, but tries, rather, to figure out how to bring things to the point of collapse. Because the system itself is what must be opposed—a representative democracy within which only rich, white people are represented. A legal system within which the law preserves the rights of the exploiters. A medical system in which the rich get treatment and doctors deal drugs, and poor people die “prematurely,” as Ruth Wilson Gilmore puts it. I am not a political theorist—duh!—but I do think that this is an interesting moment to think beyond state-oriented democratic politics.

DRY: Yes. I see.

JH: A part of the anarchist orientation to politics involves principled refusals and abolitionist orientations to institutions like the prison, the university, the law, and the state. The Invisible Committee, an anonymous collective in France, argue that “institutions are obstacles to organizing ourselves.” I do think that something that we’re calling anarchy or the undercommons, or waywardness takes us out of a logic that always reorients to respectability and collusion and recognition.

DRY: In the vertiginous capital piece, you say it is time for “new tactics: fewer strategies of repair and more damage to the system; less fixing up and more taking down; fewer victims and more fighters.”

JH: Yes, my new work is about tearing things down in the mode demonstrated by Gordon Matta-Clark’s anarchitectural projects. He trained as an architect in order to practice as an anarchitect—the anarchitect does not simply want to dismantle everything, they want instead to figure out how to bring structures to the point of collapse. That appeals to me. The question that seems most pertinent now, in an era of environmental decline, financial corruption, right-wing populism, is, for me, how do we unbuild the world? Queer theory in the mode that Eve K. Sedgwick and even José E. Muñoz espoused was very committed to world making. I honor that lineage and queer genealogy, but I also want to turn for a while towards world unmaking. Another world is possible, but only when this one ends.

DRY: I love it.

JH: And that is probably a wrap.