04 May Nearly every mass killer is a man. We should all be talking more about that

From the Oklahoma bombing to the massacre in Norway it is always the same. In the immediate aftermath of mass murder, the initial hypothesis is that it must be a Muslim. And so it was on Monday that, within minutes of a van mowing down pedestrians in Toronto, a far-right lynching party was mobilised on social media looking for jihadis. Paul Joseph Watson, of conspiracy site Infowars, announced, “A jihadist has just killed nine people”; Katie Hopkins branded the Canadian prime minister, Justin Trudeau, a “terrorist shill”.

But there is a far safer assumption one can generally make. For while a relatively small proportion of mass killers in North America are Muslim, across the globe they are almost all men.

There will be, though, no appeals for moderate men to denounce toxic masculinity, no extra surveillance where men congregate, no government-sponsored schemes to promote moderate manhood, or travel bans for men. Indeed, the one thing that is consistently true for such incidents, whether they are classified as terrorist or not, will for the most part go unremarked. Obviously not all men are killers. But the fact that virtually all mass killers are men should, at the very least, give pause for thought. If it were women slaying people at this rate, feminism would be in the dock. The fact they are male is both accepted and expected. Boys will be boys; mass murderers will be men.

This week’s atrocity in Toronto, where Alek Minassian stands accused of killing 10 and wounding 14, gives us yet another chance to reflect on the destructive capacity of masculinity – not least because it may have been the principal motivefor this attack.

Minassian is not known to have any strong religious affiliations. But according to his Facebook feed, he identified with devotees of “incel” (short for “involuntarily celibate”), which is for straight men who “can’t have sex despite wanting to” and splits the world into Stacys (attractive women who won’t sleep with them) and Chads (men who are sexually successful).

It seems innocent and adolescent – that blend of pathos and priapism that helped get nerdy boys through high school. Only, Minassian was 25 and hadn’t grown out of it, but into it with a vengeance. His last Facebook post read: “The Incel Rebellion has already begun! We will overthrow all the Chads and Stacys! All hail the Supreme Gentleman Elliot Rodger!”

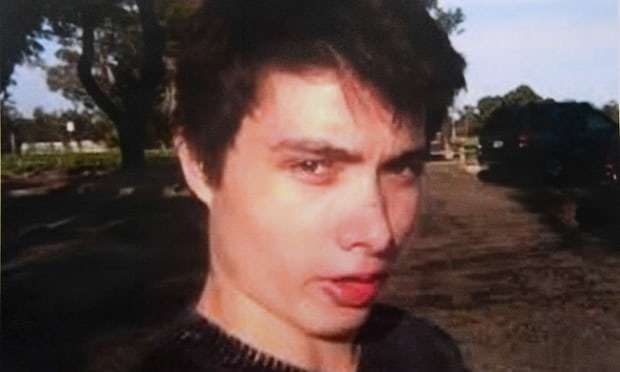

In 2014, 22-year-old Rodger wrote a screed against, among other things, women and couples (particularly inter-racial couples), before killing seven people, including himself, and injuring 14 in Isla Vista, California. “I don’t know why you girls aren’t attracted to me but I will punish you all for it,” Rodger stated in a video uploaded before the rampage. “It’s an injustice, a crime because … I’m the perfect guy and yet you throw yourselves at all these obnoxious men instead of me, the supreme gentleman.”

Alexandre Bissonnette, who killed six and injured 19 in a mosque in Quebec City last year, identified with Rodger and had been Googling him not long before the crime.

With tens of thousands visiting their message boards, incel is hardly marginal – though arguably too amorphous and incoherent to dignify with the term movement. It is debatable how widespread the cult of Rodger might be. But the issues of misogyny and inadequacy that drive men to it characterise a far broader and deeper problem that helps to explain male violence.

On the one hand, there is the hatred of women, born for the most part from a sense of entitlement. These men do not just resent the fact that they can’t get a girlfriend. They feel women are denying them the sex that is rightfully theirs. They belong to broadly the same demographic as the Gamergate movement earlier this decade, in which male gamers systematically harassed female game developers and media critics, subjecting them to rape and death threats, and publishing details of their personal lives online.

These men, wherever they are, now have more political space than they used to. There is considerable overlap with the American hard right. And they have a role model in the White House in a president who was accused of rape by his first wife, boasts of grabbing women by the genitals, makes up sexual stories about womenon the internet, and openly disparages their looks and intellect. In the 2005 book TrumpNation, the future president tells Timothy O’Brien his favourite part in Pulp Fiction is when “Sam [Jackson] had his gun out in the diner and he tells the guy to tell his girlfriend to shut up: ‘Tell that Bitch to be cool.’ Say, ‘Bitch be cool.’ I love those lines.”

We don’t know what proportion of these men go on to have abusive relationships or if they enter relationships at all. But we do know there is a significant correlation between domestic abuse and mass murder.

An Everytown for Gun Safety report last year revealed that between 2009 and 2016 more than half of mass shootings in the US were related to domestic or family violence. In a third of the public mass shootings during that time period the gunman had a history of violence against women – domestic abuse is a more common trait among mass murderers than mental illness.

On the other hand, there is a deep sense of grievance. While most people avoid association with failure, these men are attracted to it. Their inadequacy is central both to their identity and their rage. They are not the men they want or need to be; they do not have the status they feel was their birthright. This is the fault of others and somebody, anybody, must therefore pay. “The amok man,” writes Douglas Kellner in Guys and Guns Amok, describing the man likely to commit a mass killing, “is patently out of his mind … But his rampage is preceded by lengthy brooding over failure and is carefully planned as a means of deliverance from an unbearable situation.”

While the desire to dominate and the embrace of failure may appear contradictory, they are in fact part of the same pathology. The rage stems from the fact that the very thing they feel entitled to – women’s bodies, women’s lives, women’s obeisance – is not available to them. They hate the thing they cannot have. And of course they hate themselves for their inability to get it.

If ever there was an illustration of how a system of patriarchy demeans and depletes us all, this is it. Unable to take advantage of the male privileges they believe they are owed, they feel inadequate and grow resentful, and a handful become violent. Often awkward, shy and unconfident, they cannot meet the standards of machismo that patriarchy demands. They think feminism will destroy them. But in fact it is their greatest chance of liberation, since the less women are forced to conform to preconceived notions of femininity, the more space there is within masculinity for them to be themselves. As such, they are not only the perpetrators of misogyny but the products and, ultimately, the victims of it.