30 Mar An alternate history of sexuality in club culture: Part 1

Dance music was born in LGBT communities, but has this been forgotten? In this extended feature, Luis-Manuel Garcia examines the history of club culture’s queer roots.

Maybe we need to flip the opening question on its head: if the roots of electronic music are so sexually diverse, why do today’s audiences need to be reminded of it? Have we forgotten about the queer nightlife worlds of the ’70s and ’80s? That’s the problem according to Loren Granic, AKA Goddollars, co-founder and resident of A Club Called Rhonda in Los Angeles, who doesn’t mince words:

“We’re currently experiencing a total mainstreaming of dance music in America,” he says. “Many of these newcomers are straight/white kids who are very far removed from the LGBT community, despite fist-pumping by the millions to a music that was born from gay people of color sweating their asses off at 5 AM in a Chicago warehouse. It’s easy for us to dismiss this as a corruption of the music we hold so dear by charlatans and assholes, but many of the newcomers will be drawn into the music for life, and I think it’s important that we highlight the role that the gay community played and that we educate new fans of dance music to the ideals of community, equality and diversity that were so crucial to dance music’s DNA from the beginning.

Loren Granic, Gregory Alexander of A Club Called Rhonda

“And if sexual minorities were historically central to the emergence of dance music culture, where are they now? If you take a look at who is running the clubs, managing the labels, booking the artists, and playing the records, the demographics are starkly different from the crowds that got this music started. Considering how big a role the gay community played in the genesis of the music, it’s strange to see that the majority of the stakeholders nowadays are of the straight male variety. It would be great to see promoters, artists, producers and club owners take a stronger stand to be more inclusive of the culture from which they take and profit so liberally.”

Despite this, queer dance music scenes continue to thrive today, even if they’re mostly off the radar of mainstream dance music media. Why and how did that happen? Part of this might have to do with the scale of today’s club culture: it’s easier for minorities to remain central to a music scene when it’s small, local and personal. Once it becomes a massive global phenomenon, it’s much harder for marginalized people to stay inside the frame of attention. But another reason for this absence is that history is written by victors: as dance music became more mainstream and had more crossover success, the people writing its history followed the “more relevant” threads into primarily straight, white, middle class environments, quickly forgetting about the more queer and colorful scenes that were still dancing and making music.

These days, it’s clear that there is not one history but many histories. Everyone has an idea of how things happened and, as more people have access to writing, publishing, the internet, etc., more and more alternative histories crop up to contest the “official” version of events. Those who want to uncover the history of marginalized peoples have to search through the archives of historical documents—mostly written by the powerful about the powerful for the powerful—to find traces of what the less powerful were doing. The idea behind this feature is not to set the record “straight,” but rather to re-examine club culture’s queer roots, and then dig up the stories of the scene’s queer undergrounds.

New York disco and garage /

In New York City at the beginning of the 1970s, queers of color (primarily of African-American and Latin-Caribbean ancestry) and many straight-but-not-narrow allies came together to create small pockets of space in the city’s harsh urban landscape—spaces where they could be safe, be themselves, be someone else for a while, and be with others in ways not permitted in the “normal” everyday world. Music was an essential part of these gatherings, and the sound of these events would eventually develop into the style called disco. The sound was a mix of soul, funk and Latin music with a driving, four-four kick drum pattern. It took its name from discotheque, the French word given to nightlife venues that featured recorded music instead of live performances.

But disco didn’t start in discotheques; most histories of disco start with The Loft, David Mancuso’s series of private parties held in his apartment in the Lower East Side of Manhattan. Mancuso was DJ, promoter and master of ceremonies from the beginning to the end of the night, presiding over a crowd of mixed sexualities, gender expressions, ethnicities and social classes. As word got around about Mancuso’s parties, discotheques in Lower and Midtown Manhattan began to cater to this emerging sound, such as Nicky Siano’s The Gallery. By 1973, this sound had become prominent enough for music journalist Vince Aletti to pen the first article on disco (“Discotheque Rock ’72: Paaaaarty!”), for Rolling Stone magazine. In it he described the local disco scene as a thriving underground of “juice bars, after-hours clubs, private lofts open on weekends to members only,” populated by a “hardcore dance crowd—blacks, Latins, gays.”

Later in the ’70s, disco gained in popularity and developed a larger presence in the above-ground nightlife economy, spilling over into mainstream discotheques, being broadcast on national and international radio, and gradually attracting a larger audience of white, straight, middle class people. This was the time when many purpose-built disco clubs started opening, such as Studio 54 (1977) and the Paradise Garage (1976) in New York, as well as the EndUp (1973) and the Trocadero Transfer (1977) in San Francisco. And this was also the period when many of disco’s best-known artists launched their careers—Donna Summer, Chic, The Bee Gees, KC And The Sunshine Band.

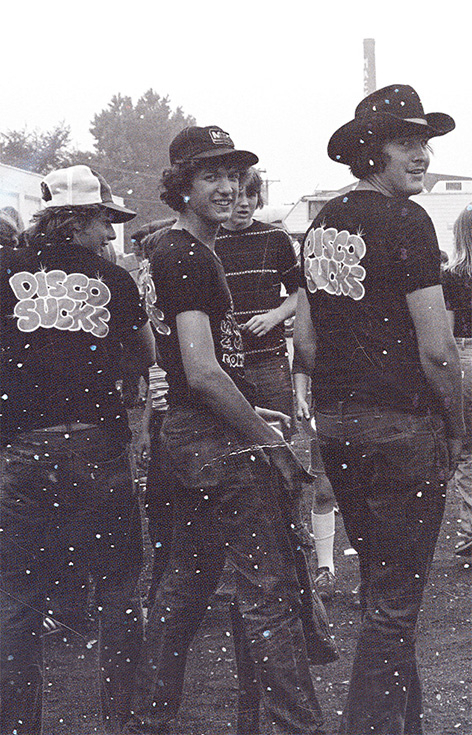

As disco recordings began to saturate the music markets, disco itself increasingly lost its connection to its queer, black and Latin roots. But these roots weren’t completely forgotten: when the disco market collapsed at the end of the ’70s and the anti-disco backlash began to take over in America, disco’s critics suddenly remembered its sexualized and racialized origins. The anti-disco slogan, “Disco Sucks”—available on t-shirts, bumper stickers, buttons and more—wasn’t just a metaphor in the ’70s: it was a direct reference to cock-sucking, aiming a half-spoken homophobic slur at disco and its fans.

In Chicago, on July 12, 1979, WLUP disc jockey Steve Dahl organized the Disco Demolition Night at Comiskey Park during a double-header between the White Sox and the Detroit Tigers. Spectators were invited to bring along unwanted disco records, which were piled into the middle of the field during the break between the two games and blown up with dynamite. Chanting “disco sucks,” fans flooded onto the field and began to riot. These collective outbursts of anti-disco sentiment were not as spontaneous or “grassroots” as the press would later make them out to be. In fact, as Alice Echols relates in her history of disco, Hot Stuff: Disco And The Remaking Of American Culture, this backlash was to a large extent organized by a handful of disgruntled radio professionals (Dahl, but also Lee Abrams and Kent Burkhart) who orchestrated a shift in rhetoric and programming across several radio stations, in order to profit from the ensuing anti-disco backlash.

But disco’s downfall didn’t happen overnight. Sales had been falling for some time beforehand, and they would continue to taper off into the ’80s. Outside of the US, disco stuck around and dovetailed with ’80s dance-pop, new wave and industrial music. Nonetheless, some of the changes were shockingly abrupt. Most of the major record labels closed down their entire disco divisions, laying off their employees and canceling artists’ contracts with almost no notice. The disco collapse hit nightclubs especially hard, and the few clubs that managed to stay open went on to form the “underground” of the post-disco era.

In New York, Paradise Garage was the most well-known of these surviving clubs, which catered to an audience that was primarily queer, black and/or Latin-Caribbean. Larry Levan, the club’s resident DJ, maintained a loyal following of dancers by developing a distinctive sound that would later be dubbed “garage.” Depending on who (and how) you ask, garage was either a precursor, a parallel or a sub-style of house music. Generally slower in tempo than Chicago house, it featured a mix of disco, R&B, soul and funk with a focus on gospel-inflected vocals. Clubs like Paradise Garage, The Saint and Zanzibar kept the post-disco tradition alive in New York and New Jersey throughout the ’80s, while newer clubs like Sound Factory and Twilo brought club culture into the ’90s.