19 Oct Squats, Sex Clubs and Punk: The Lesbian London of the 1980s

Thirty years ago, in 1987, London was a different place for LGBT people. Gay men congregated around King’s Cross, lesbians started their own S&M fetish clubs and people cruised one another at protests, not on apps. There’s a Facebook group that keeps this history alive, where gays and lesbians who used to go to a King’s Cross pub called The Bell share YouTube videos of 80s club bangers and photos of themselves wearing too much eyeliner. But perhaps most tellingly, the members of the group post pictures of the luxury apartment blocks that have now replaced their old haunts.

Filmmaker and artist Siobhan Fahey was a lesbian living in London at this time, and is currently in the process of making a film about the period: Rebel Dykes, a documentary looking at the lives of her friends – a gang of lesbian separatist punk anarchists based mostly around Brixton and its many squats. The film captures the culture war that pitted Siobhan’s sex-positive dyke crew against a bunch of uptight lesbian feminists, as well as depicting a society that was hostile towards lesbians and gays.

Ahead of this year’s Pride, Siobhan filled us in on what’s changed for lesbians in London over the last three decades.

VICE: Your film Rebel Dykes focuses on a pretty specific time and place for lesbians – London in the late 1980s. Can you start by painting a picture that takes us back there?

Siobhan Fahey: Well, Thatcher was in government, so politically the climate felt similar to now, particularly the austerity measures we’ve been living through recently. Everything seemed cold and harsh, and it felt like there was homelessness everywhere. We lived in squats around Brixton, and moved all the time when they turfed us out. There was lots going on politically that you couldn’t help but be opposed to, like Apartheid. It felt like there were demonstrations about something every Saturday. That was our social life and way of spreading news.

And what was it like being LGBT then?

Being LGBT was dangerous – people would be aghast at the idea of watching gay people kissing or holding hands in public. I remember butch women suffering a lot of violence, getting beaten up regularly. There were no role models at all. But there was a great source of excitement or fun from being the outsiders. We all stuck together, like the bad girls. We dressed in leather, had flat top haircuts, wore big boots – a very strong look so that you’d know we were a gang. We were outcasts from society, and outcasts within the wider lesbian community too.

How do you mean?

There was a big split at the time between us and women who called themselves “political lesbians”. They were so opposed to men that they thought the best thing to do was to become a lesbian. They didn’t even necessarily fancy women. They just hated anything that they thought was “aping heterosexuality”, as they’d put it; butch and femme, fantasies that involved anything masculine, power play. They were madly against dildos and very anti-porn. They were really extreme and really annoying. I think, in a way, they became what you call TERFs [trans-exclusionary radical feminists] today. The philosophers they based their ideas on were some of the same people, like Sheila Jeffreys and, later, Julie Bindel. Trans women are the enemy now, but we were the enemy then. It was very hard work, very depressing to be a lesbian at that time. We felt people were always telling us off for being lesbians or feminists in the wrong way.

What did that mean for the lesbian club scene back then? Was there one?

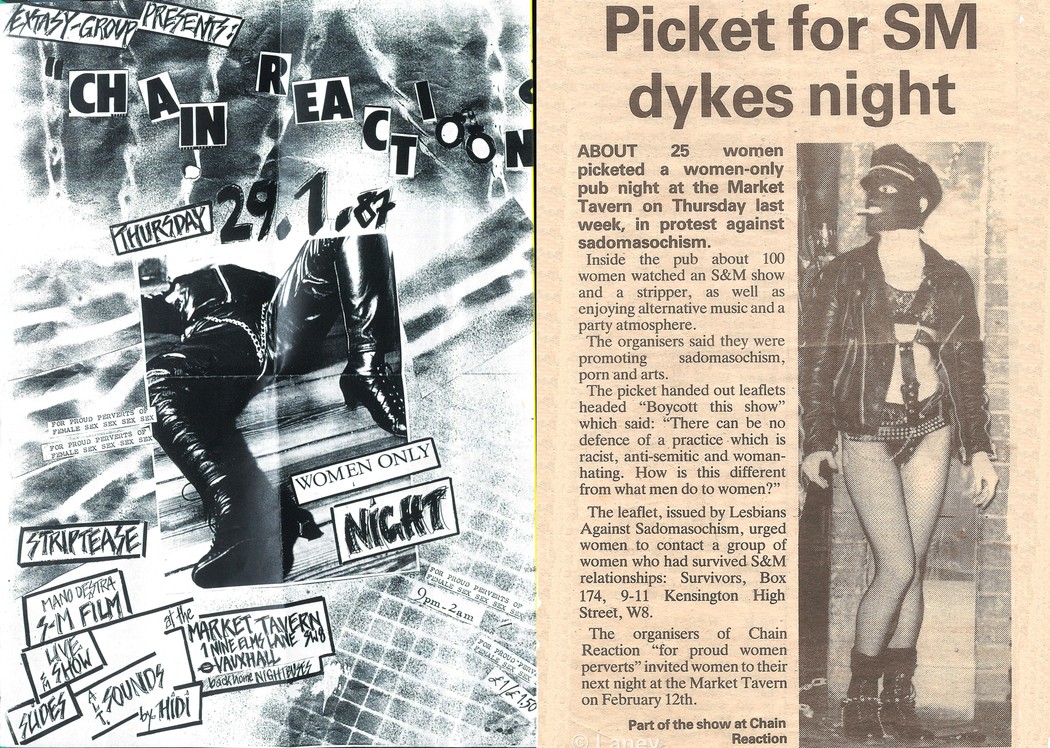

1987 was an important year, because an iconic lesbian fetish club opened that became a real home for us punk dykes, and the place where the differences between the more right-on feminists and the sex-positive punk women became very apparent. It was called Chain Reaction and was held on a Tuesday night in a gay men’s bar in Vauxhall called The Market Tavern, which has now long disappeared. I was a stripper on the first night and I remember there was lots of live sex and experimenting with S&M. Lots of leather! Someone did a sex show on a motorbike. There’s no way you’d get away with that now. It was wild. And a real community – people met lovers and friends who they have stayed lovers and friends with ’til today. I can’t imagine a gay pub packed to the rafters on a Tuesday nowadays – it just goes to show that loads of us didn’t work.

What did the political lesbians make of it?

On the first night they protested outside it. On the next one they came in and smashed the place up in balaclavas. They got chased out by leather dykes and never came back, but it hit the papers, and as we say in the film, from that moment on the club became even more popular. Looking back, I don’t think it was all about the S&M. I think people just finally wanted to be sexual in a world where being a lesbian had become extraordinarily celibate, feminist and right on. People wanted to put a finger up to that and create something more outrageous. The night only lasted a couple of years, but it had a big influence on sex-positive feminism, Riot Grrrl culture, queer core – all of those movements came out of it.

You said a lot of you were living in squats at the time; can you tell me more about that?

I squatted for years, until the early 90s when I moved out of London, and when the other women got offered hard-to-let flats. With squats, we often moved quite a lot – once every six months or a year. We lived in a lot of little flats among Tulse Hill, Brixton and Clapham that are probably million pound beautiful houses now. We would do things like get electricity from our neighbour’s house with a big wire, or switch on our own gas. Sometimes, when you moved into a house, the telephone would still be working, so there’d be queues of people outside trying to get in and call Australia.

Was it all lesbians you lived with?

We would live in women-only communes, where not all were lesbians, but most were. People would cook together, have kitties. In our house on Brailsford Road [in Herne Hill] I remember the basement was a rehearsal room for punk bands to come through. It was all quite multifunctional; one house had a creche in it, people ran cafes. 121 Railton Road in Brixton was an anarchist bookshop with a club downstairs and a cafe upstairs. A lot of people ran activist campaigns from the proceeds of club nights there.

And you said a lot of you didn’t have jobs.

Nothing was computerised, so you got away with a lot you wouldn’t now. Like with the benefit system, people would just sign on for multiple names wearing wigs and stuff. I don’t remember knowing anybody working proper jobs. I maybe knew one person who was a teacher. I worked as a stripper in the peep shows, as did a lot of lesbian women I knew, while some went into manual trade work like carpentry or plumbing.

So in a way it was the economic climate that fostered such a tight community?

Definitely. We stuck together. But that story about artists, creatives and squatters being the first step in gentrification, we did see it happening, although it was very different and much smaller. The area where us activists and punks lived in Brixton was a very black area. The police wouldn’t even go down there. But we had a Brixton Whole Foods where lots of lesbians worked. That was one of the first gentrifying shops of Brixton. It’s still there, across the street on Atlantic Road, but places you thought would never go did ages ago now. I don’t see how you can have a tight community like we had when you just don’t have the space in London today – it’s too expensive. I live in Manchester now, and it feels like here and in Glasgow we can still do DIY club nights, live in big houses or co-ops altogether – it’s just the same.

What are your memories of Pride back in the late-80s?

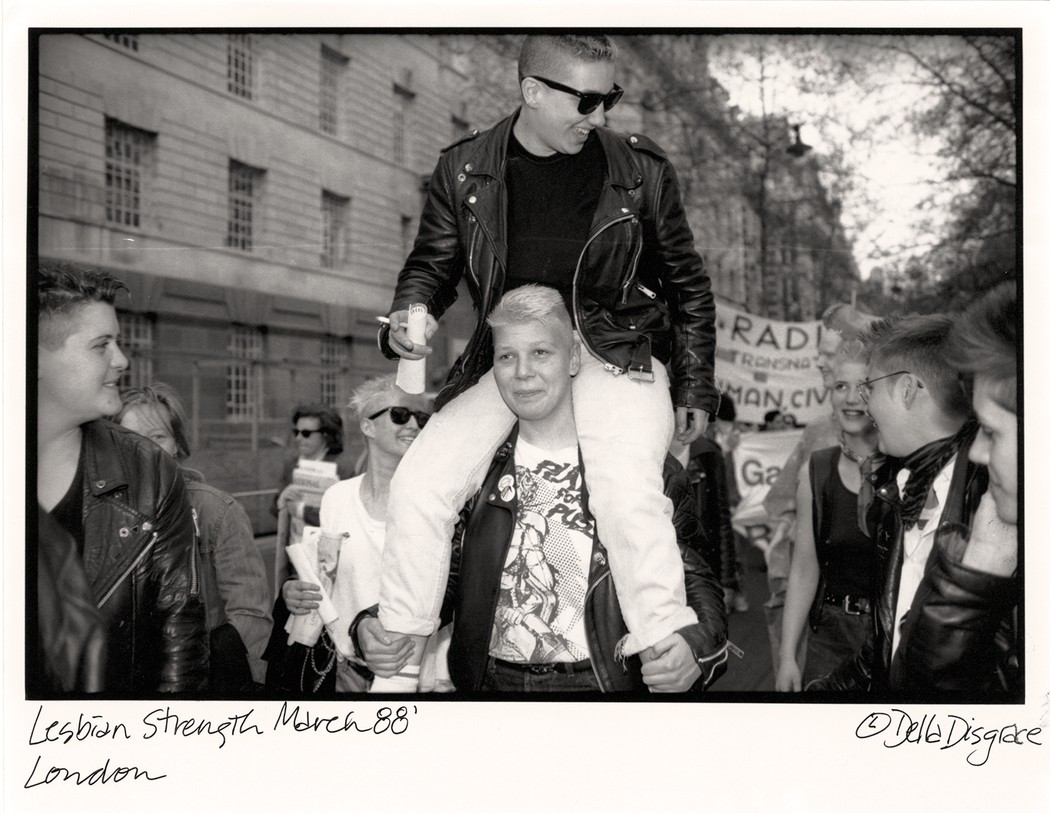

Pride was very different. Much smaller. The first Pride I went to we ended up at Jubilee Gardens by the Thames, and it was a tiny bit of grass and all of the acts were local, community bands. It was great fun. The walk through the city wasn’t so much about marching and waving flags. People would be staring at you, so there was all the more reason for our women to look more extreme with our boots and our chains, to really put what we were in their faces.

Were the political lesbians there too?

Not at Pride, but there was a Dyke March, and a famous one in 1987 or 1988 where the fetish lesbians and punk gangs turned up with banners, and first of all we were sent to the back –people wouldn’t let us on the march and were handing out leaflets against us – but then the march started being followed by a bunch of fascists, and because we looked a lot harder we ended up leading the march after all, to scare them off.

Lastly, what’s the biggest change you’ve seen in lesbian culture over 30 years?

I don’t think it’s changed that much, in a way, because the two-sided thing in the community feels the same. My personal queer female community is very similar, with women living in co-ops and in punk bands. But sometimes I go on those lesbian vlogs they have online and it just seems too foreign… all those straight-looking young women with long hair – I mean, they’re not queer, are they? It’s like we were waiting for it all to get more acceptable and now things are just a bit dull. I mean, Facebook is currently trying to ban the word “dyke” [the site has been deleting posts that use the word]. I think everyone should put “Dyke” on their Facebook status.