24 Sep The Women Who Built Socialist Yugoslavia

by Theodossis Issaias and Anna Kats

Editor’s Note: To American ears, the mention of Yugoslavia—the former federation containing six Balkan republics and Kosovo—evokes bombing campaigns, bloody ethnic strife, and the resounding failures of 20th-century socialism. Yet for decades after its breaking with Stalin’s USSR in 1948, and later, its brokering of the Non-Aligned Movement, Yugoslavia had been a prosperous country, uniquely positioned between the West and East and oriented toward the Global South.

Toward a Concrete Utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia, 1948–1980, the debut exhibition from MoMA‘s chief curator of architecture and design Martino Stierli, documents how buildings and the people behind them contributed to the modernization and social cohering of a historically multi-ethnic region. The following essay in particular highlights influential women practitioners from the period and their startlingly original works.

In socialist Yugoslavia’s founding narrative, the woman partisan had won her emancipation with the rifle. The activities of the Women’s Antifascist Front during World War II, which extended from the armed fight to grassroots political organization, advanced feminist causes and solidified women’s position in the creation of the socialist federation. With the transition to civilian life, Yugoslavia’s first postwar constitution of 1946 unequivocally granted Yugoslav women full citizenship, both by guaranteeing voting rights to all citizens regardless of sex and by providing special protection for women’s place in the production process. It also adhered to one of the fundamental tenets of the socialist-Marxist ideology; that is, women’s emancipation depended on the egalitarian distribution of wealth and vice versa.

Yet, systemic disparities persisted. Gender inequality was not recognized as an autonomous issue but was, rather, subsumed under the general discourse of class struggle and self-management. Such a position hindered women’s advancement in leadership positions, and the architectural profession proved no exception. The few women architects who ultimately commanded public profiles did so in spite of, not through the dismantling of, both the region’s and the profession’s male-dominated cultures. The contributions of women architects—who have so often been omitted from the histories of socialist Yugoslavia’s architecture—must then be seen in relation to the successes and failures of this constitutional promise of equality.

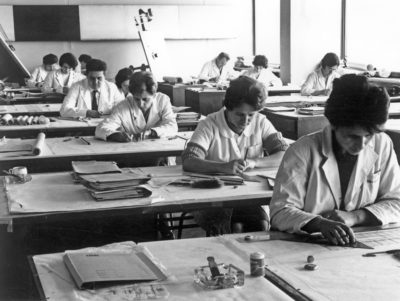

The remarkable breakthroughs women made in the decades after World War II cannot be ignored. Their enrollment in higher education steadily increased for the first three decades after the war; by 1962, 45 percent of graduates from the Faculty of Architecture in Zagreb were female. Women’s presence in the workplace also increased; if women made up 24.5 percent of the active workforce in 1948, they accounted for a full third by 1978. But these advances were not enough to erode reactionary presuppositions about gender roles both within the household and the labor market. As late as 1971, women held less than 10 percent of management positions. At the same time, the nuclear family in which both parents were employed had become the fundamental economic unit in socialist Yugoslavia, and while legal provisions like paid maternity leave eased some of the family burden, unpaid labor within the household remained almost entirely a woman’s task.

The comprehensive restructuring of the domestic environment, encompassing all scales from the individual apartment to the neighborhood preoccupied the postwar generation of architects. It was that very effort to reform housing and the domestic sphere through design research, publications, and didactic exhibitions where women practitioners often took the lead, building on the legacy of the previous generation of women who had entered the architectural profession by way of interior design and the applied arts. Architects such as Branka Tancig Novak (1927–2013), who pioneered the design of prefabricated kitchens, for example, thus focused their attention on the modernization of the household.

Indeed, individual studio practice, and the degree of authorial credit that it bestowed, often proved an untenable professional model for women, and they often entered the profession as employees in research institutes or in design departments embedded in large-scale construction companies. Mimoza Nestorova-Tomić (b.1929), for example, assisted at the Institute for Planning and Architecture in Skopje, working closely with Kenzō Tange’s team on the reconstruction scheme for the Macedonian capital in the aftermath of a devastating earthquake in 1963. A prolific architect—she designed the celebrated Museum of Macedonia (1963–72) with Kiril Muratovski (b. 1930)—Nestorova-Tomić became the Institute’s director two decades later.

Milica Šterić (1914–1998) represents the apogee of this trajectory for women. In 1947, after working briefly at the Ministry of Construction, she went on to oversee the Department of Architecture and Urbanism at the state construction firm Energoprojekt, which was charged with many important infrastructure projects throughout Yugoslavia and abroad. Her adroit management steered the company’s complex geopolitical relations across Africa, the Middle East, and domestically, enabling her ascent up the corporate hierarchy to occupy an executive seat on the Energoprojekt managing board. She eventually became the Assistant Director General of the entire company and designed the first Energoprojekt Headquarters (1956–60). The commanding presence of the complex’s 13-story tower and advanced installation of curtain-wall systems announced the company’s technological ambitions and served as a branding tool.

As the prolific principal designer and proprietor of her own studio, Montenegrin-born architect Svetlana Kana Radević (1937–2000) was the rare exception to the norm of women designers who often remained anonymous collaborators. Radević graduated from both the Faculty of Architecture and the Art History department of the University of Belgrade, and won the competition to design the Hotel Podgorica (1964–67) in the Montenegrin capital shortly thereafter. She rose to national prominence in 1967 when she won the federal Borba Prize for Architecture for the project. The building follows the undulating bank of the Morača River along which it stands, enabling a symbiotic relationship between plan and site. Truncated three story walls, impregnated with local river pebbles, frame the residential quarters and the common facilities, and their materiality further reconciles landscape and building. The project underscores how Radević not only absorbed formal tendencies from contemporary Brutalism but invented an idiosyncratic formal lexicon, which she continued to develop after she won a Fulbright scholarship to study with Louis Kahn at the University of Pennsylvania in 1972. (Radević was one of the many Yugoslav architects to temporarily study or work in the West—in some cases, alongside practitioners such as Kahn and Le Corbusier.) After her return to Yugoslavia, she designed a great number of projects, most notably the Hotel Zlatibor (1975–81), a monolithic concrete tower in the western Serbian city of Užice. An active agent in global architectural networks, she worked with the Metabolist architect Kisho Kurokawa in Tokyo and was elected a foreign member of the Russian Academy of Architecture and Construction in 1994.

Today, Radević’s Hotel Podgorica and Šterić’s Energoprojekt Headquarters are under threat: the contextual integrity of the former is endangered by the construction of an adjacent 12-story tower, and Šterić’s building, stripped of its original facade, exists only as a concrete skeleton. A new historiography of Yugoslav postwar architecture cannot alone salvage these architects’ built work, but it stands to reassess their respective legacies. Radević’s hotels, Tancig’s prefabricated kitchen, Ivanšek’s research surveys, Šterić’s managerial legacy, and Nestorova-Tomić’s urban plans and museums all testify to the multitude and diversity of these architects’ achievements in socialist Yugoslavia. Those practitioners who claimed agency and shifted professional paradigms did so even as the architectural profession failed to cultivate parity.