13 Apr AN ALTERNATE HISTORY OF SEXUALITY IN CLUB CULTURE: PART 3

Queer undergrounds /

This revised history of the disco and early post-disco era only scratches the surface, and it admittedly leaves out a whole range of other scenes and genres that are usually part of the history of electronic music. But there are also many other histories that need to be told, too. If the stories of marginalized peoples tend to disappear from the “official record” of history, then we need to look closely at those historical fragments that don’t easily fit into this dominant narrative.

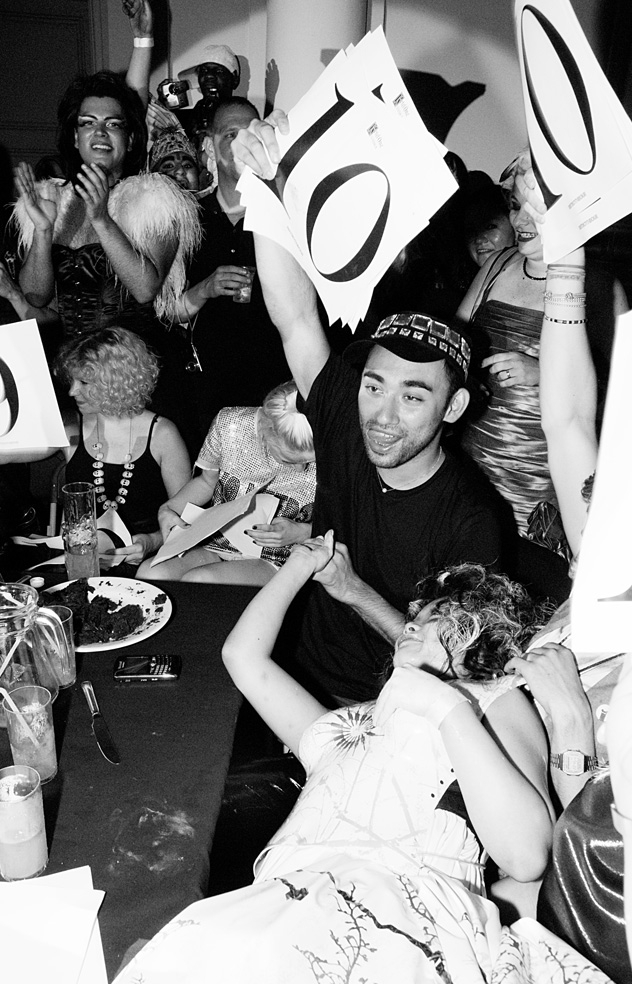

Drag balls /

One of these is the history of ballroom culture, a mixture of music, dance, performance art, fashion and personal reinvention. At the heart of it is the drag ball, a combination of beauty pageant, fashion runway and dance competition rooted in historically-marginalized transgender communities. Ball culture of some sort can be traced at least as far back as the Harlem Renaissance of the 1930s, when costume balls provided the opportunity for partygoers to circumvent New York’s strict laws against cross-dressing and same-sex dancing. In the 1970s, people in the drag ball scene began to organize themselves into “houses,” families-by-choice that would compete as a team at balls, share resources, practice their routines together and often live under the same roof. This scene came to public attention at the beginning of the 1990s, thanks to three things: the release of Jennie Livingston’s poignant documentary on New York’s ballroom scene, Paris Is Burning; gender scholar Judith Butler’s analysis of this documentary and other drag events as part of her influential theory of gender performativity; and Madonna’s hit dance single “Vogue,” named after vogueing, ballroom culture’s emblematic dance style.

Drag balls have been both a living archive of the post-disco era and a crucible for new styles of music and dancing, which has gone on to influence dance culture far beyond the usual circuit of nightclubs. Most—perhaps nearly all—of the dance moves you see in R&B and pop videos today come from choreographers who have been involved in ballroom culture. In the ’90s, the ballroom scene even developed its own sub-style of high-intensity house music, such as Tronco Traxx’s “Walk For Me,” Kevin Aviance’s “Cunty,” E.G. Fullalove’s “Didn’t I Know (Divas To The Dancefloor…Please),” and Masters At Work’s classic “The Ha Dance,” which went on to form the basis of an entire genre of vogueing track, called “ha tracks.”

Drag balls have historically been the domain of queers of color, although there has always been a minority of white, straight and/or cisgendered participants. In particular, these scenes give transgendered people spaces where they can enjoy a degree of social prominence and cultural authority. They’re not only central as performers and bearers of a living tradition, but many also hold positions of power within these scenes. And drag balls play an important role as places of recognition for the socially-marginalized: all of the competitive elements taken from beauty pageants—from trophies to tiaras—can be understood as a response to the rejection and humiliation queer folks endure in daily life.

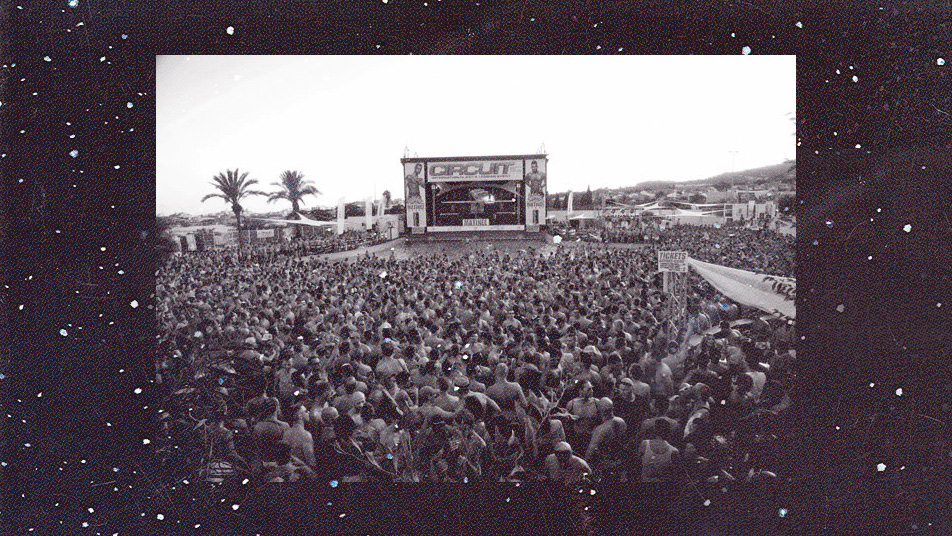

Circuit parties /

In many ways, circuit parties seem to be the polar opposite of drag balls. Instead of small-scale, community-organized events held after-hours in old banquet halls and attended mostly by poor, underprivileged, gender-queer people of color, circuit parties are large-scale, corporate-sponsored mega-events held in massive locations and populated mostly by affluent, predominantly white gay men. They grew out of the tea dances and seasonal parties that had been taking place at Fire Island, Provincetown, and other gay resort areas that had developed along the East Coast, after New York’s Stonewall riots in 1969 made sexuality a publicly-debated civil-rights issue in the US. Over the 1980s, these parties developed into a circuit of massive, all-night dance music events spread across gay tourism destinations and certain cities (Montréal, New York, Miami, New Orleans, San Francisco, Toronto). The sound of “the circuit” was originally hi-NRG and early house, but across the ’90s it turned towards hard house, tribal house and trance.

Some writers have described circuit parties as “gay raves” (for example, see the last chapter of Silcott’s Rave America), which is neither entirely false nor entirely true. On the one hand, raves and circuit parties have a few things in common: all-night running hours, a focus on sample-based dance music, the prominence of club drugs like ecstasy, and overpriced energy drinks. On the other hand, circuit parties distinguish themselves from raves by their exclusive focus on particular sexual identities, and their levels of professionalization and commercialization. Very early in their development, circuit parties became large-scale, lucrative, commercialized affairs run by professional teams (of mostly white and/or gay men), often with corporate sponsorship—alcohol and tobacco companies being the biggest, although companies that produced condoms, gay porn and sex toys were often sponsors.

Deep house in Midtown Manhattan /

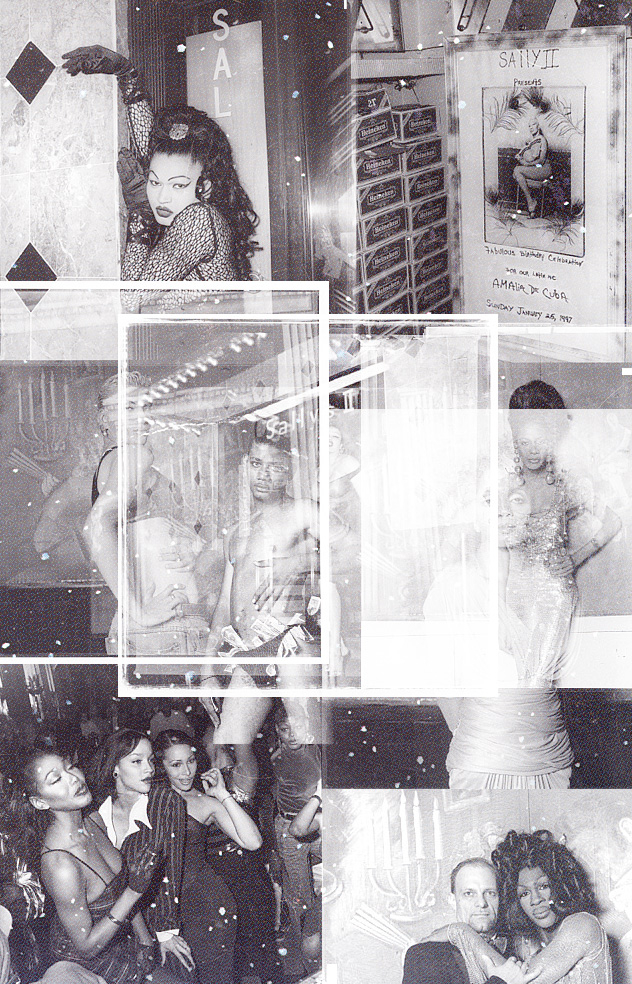

Back in 2009, Terre Thaemlitz released the album Midtown 120 Blues, under the name DJ Sprinkles. The album’s title conveys at least three layers of meaning: the red light district along 42nd street in Midtown Manhattan, which offered gathering places for sexual outcasts, especially transpeople and sex workers; 120 beats per minute, the relatively slow tempo of New York’s deep house sound in the ’90s; and the blues, another African-American musical tradition that focuses on melancholia instead of euphoria to engage with everyday problems. Thaemlitz worked as a DJ for a few years during the early ’90s at one of the transgender clubs along the Midtown strip, Sally’s II. Clubs along this strip were doubly marginal, as other queer scenes disapproved of the sex work that often went on there. “Sally’s II and Edelweiss were the two main trans-worker clubs I knew of,” says Thaemlitz. “Performers at East and West Village clubs often considered themselves ‘artists,’ and I heard more than a few rants against the Midtown ‘whores’ by stage queens at The Pyramid—which gave rise to the Deee-Lite and RuPaul scene.”

Thaemlitz is a multi-genre composer-producer, essayist, transperson, political activist and educator, who grew up in Missouri, moved to NYC during the late ’80s and early ’90s, and eventually relocated to Tokyo as Manhattan’s underground queer music scenes dissolved under gentrification. She got her start in music as a fan of disco and “techno pop” in Missouri, which left her feeling isolated from her peers, who were more focused on guitar-based rock. By the end of the ’80s, he left the violent homophobia and genderphobia of his hometown to move to NYC, although he soon found the city’s techno clubs to be “oppressively white and straight,” and male-dominated as well. “In contrast to New York’s techno scenes,” says Thaemlitz, “its house scenes were where disco, queerness, racial diversity and gender diversity were more blatant. Not always peaceably, but openly. A lot of the deep house from NY and NJ that came out at the end of the ’80s was a kind of bridge between those two sensibilities of disco and techno pop that I grew up with.” She got into DJing by making mixtapes and spinning at benefits for political activism groups like ACT-UP, who were central to the public debate about HIV/AIDS in the ’80s.

But Thaemlitz began producing at a time of personal crisis. In 1992, she lost her DJ residency at Sally’s II for refusing to play major label records, many of the political activism groups she had been involved in were falling apart, and her social connections were crumbling around issues of gender, sexuality, race, ethnicity and so on. “So everything in my life just fucking imploded. And it was in that period that I began producing my own tracks, as a pretty jaded and cynical person.”

The ’90s was a time of crisis for many of the city’s outcasts. Under the mayorship of Rudolph Giuliani, Midtown Manhattan underwent a program of “Disneyfication”: a wave of inner-city gentrification, often aggressively enforced by police violence and bureaucratic pressure.

“It was so bizarre,” reflects Thaemlitz. “Around 1997, Disney just came in and bought 42nd Street. Literally. The sex district was gone within just a few months. I remember Disney had one of their fucking electric parades down 42nd, and they had so much political clout that the city actually turned off all the streetlights for them. I mean, that may not sound like a big deal, but to anyone who did activist work and had heard endless bullshit from cops and city officials about safety regulations, fire codes and all kinds of crazy shit to limit the movement of protestors, it really laid bare the relations between commerce, politics and the construction of mobility within ‘public spaces.'”

Lesbian clubbing in Paris /

In most cities, men—especially as organizers and DJs—dominate queer dance music scenes, but Paris has been a significant exception since the late ’90s. Queer women have played important roles in electronic music, contributing as DJs, event promoters, bar staff and fans. One of the most prominent artists to come out of this scene is Jennifer Cardini, a DJ, producer and label boss for Correspondant. She got her start as a resident DJ at Le Pulp, a lesbian club that played a key role in promoting women’s involvement in electronic music in Paris. When Le Pulp opened in 1997, the club’s founder was roommates with the local lesbian DJ icon DJ SexToy (Delphine Palatsi). SexToy had been hanging out with Cardini and Fany Corale from Kill The DJ, Fabrice Desprez from Phunk Promotion and Ivan Smagghe. She brought them together to form Le Pulp’s team of DJ residents. “The energy of the Parisian lesbian scene at the time was quite exceptional,” Cardini recalls. “In Le Pulp we had created a place that was packed with girls having fun together, who felt sexy being lesbians—and where boys loved to come and would behave themselves!”

Cardini also credits Le Pulp with attracting lesbian clubbers while maintaining an open-door policy that brought in a more mixed crowd: “Everybody came from different cities, had a different sexuality, a different class and educational background. There was a big sense of community, despite all the differences. Black, trans, Arabic, lesbian, lost tourists, gay boys, hipsters, working class—they could all get in.” During the ten years it was open, Le Pulp introduced a whole generation of queer women to electronic music, inspiring many of them to become more involved in the scene. Aside from the residents of Le Pulp, many other queer female DJs have since developed a high profile in Paris and beyond: Chloé, Maud Scratch Massive, Fantômette, Léonie Pernet, and Ragnhild Nongrata.

Le Pulp eventually closed in 2007, when its building was bought up by the city for a housing project. But its closure spawned a new generation of women-led promoters and venues. “A lot of lesbian collectives have been created in these past few years, especially since the closure of Le Pulp,” says Ragnhild Nongrata, founder and manager of the Barbi(e)turix collective, which includes a fanzine, website and an event series. “Everything from small parties in bars to big club events.” Some post-Pulp lesbian “éléctro” venues include Le Troisième Lieu and Rosa Bonheur (with former members of Le Pulp’s management team), and there’s a much longer list of female-led promotion collectives, such as La Petite Maison Éléctronique, La Babydoll, Corps vs. Machine, Barbi(e)turix, Ladies Room, Kill The DJ, and many others. Many other Parisian clubs also have an important female contingent—Le Rex and Concrete. But, much like the Midtown transgender scene in NYC, Paris’s lesbian scene has been under intense pressure from rising property values and operating costs—especially in Le Marais, Paris’s historical gay and lesbian district. La Babydoll and Le Troisième Lieu have both stopped operating, while many collectives have been on indefinite hiatus.

To be continued…