07 Apr An alternate history of sexuality in club culture: Part 2

Most histories of Chicago house begin with Frankie Knuckles, a disco DJ from NYC who played records with Larry Levan at the Continental Baths, a gay bathhouse in downtown Manhattan. Levan had been offered a job as the resident DJ of a new nightclub that Chicago promoter Robert Williams was opening in the city’s West Loop in 1977, but Levan was already committed to a permanent residency at the Paradise Garage. Levan recommended Knuckles, who relocated to Chicago and took charge of the music at The Warehouse, a dance club that would cater primarily to gay black and Latino men. When the club doubled its entry fee and went upmarket in 1982, Knuckles left The Warehouse and started his own club, The Power Plant. Not to be outdone, The Warehouse responded by renaming itself The Music Box and hiring DJ Ron Hardy as its new resident.

Knuckles, Hardy and numerous other producers and DJs in Chicago at that time would go on to become the founders of Chicago house. Chicago’s house sound was developed for and in the city’s primarily queer and black clubs, mixing older disco with Italo disco, funk, hip-hop and European electro pop. In contrast to NY garage’s heavier gospel and soul influences, Chicago house drew deeply from funk music, with a more high-energy “jacking” sound that featured driving percussion and higher tempos. In the late ’80s, house music took a harder and darker turn, as DJs and producers began to experiment with the overdriven, squelching sounds of the Roland TR-303 synthesizer. This gritty, psychedelic sub-style came to be known as “acid house,” and it would later provide the initial soundtrack for the UK’s acid house party scene at the end of the decade.

The growing popularity of house and acid house in the UK brought not only record sales but also gigs for Chicago’s DJs, who found themselves traveling frequently to Europe to play for primarily white and straight crowds, while the music scene they came from continued to be largely ignored by the local American music market. And so, despite what happened at the Disco Demolition Night in 1979, disco didn’t die in Chicago. It just went back underground into the queer dance scene and returned as stripped-down, jacking, raw house music.

Detroit techno /

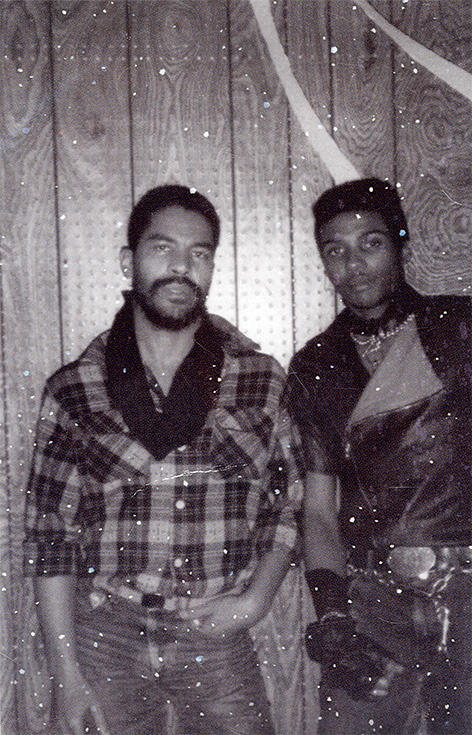

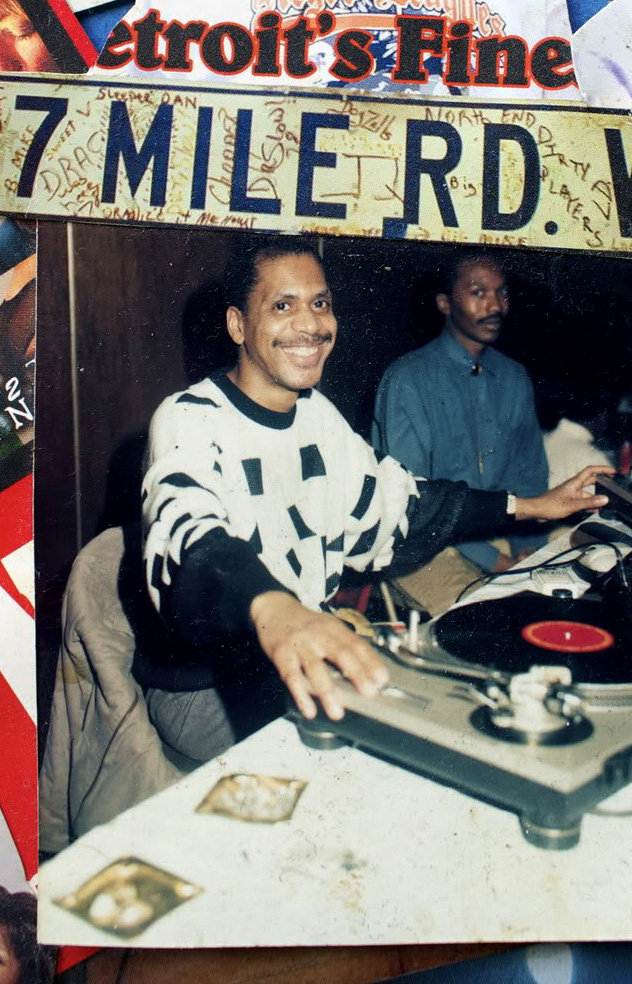

But was Detroit such a straight scene? “Compared to Chicago, I guess it kind of makes sense,” says Carleton Gholz, a Detroit-based scholar, writer and music historian, “but it’s just not true.” In his forthcoming book, Out Come The Freaks: Electronic Dance Music And The Making Of Detroit After Motown, Gholz argues that sexuality has played an important role in the development of Detroit’s post-Motown musical landscape. Instead of starting with May, Atkins and Saunderson, Gholz starts with Morris Mitchell, a DJ who was spinning disco in Detroit as early as 1971. Along with Ken Collier and Renaldo White, Mitchell formed True Disco Productions, a party outfit that organized disco events. For years, they would spin at the Chessmate, a coffeehouse from the beatnik era that turned into an after-hours gay club on the weekends.

They were part of a generation of primarily black and gay DJs that brought new DJ techniques and sounds from places like NYC and Chicago. Throughout the ’70s, Detroit’s dance scene was divided along sexual and racial lines: Ken Collier used to play at the Downstairs Pub, in the basement of the upscale disco club L’Esprit, but it was the set lists of the white DJ upstairs that appeared in Vince Aletti’s “Disco Files” column. Collier would later go on to hold a Saturday night residency at the gay after-hours club Heaven until his death in the mid-’90s. Gholz reports that many of Detroit’s “techno pioneers” saw Collier as a mentor and “godfather” of DJ culture in the city, but he gets little more than a passing mention in the history books (see Energy Flash and Techno Rebels).

And yet, this generation of disco and post-disco DJs—playing mostly in queer venues and participating in that community—played a pivotal role in the development of Detroit techno, bringing new sounds from places like NYC and Chicago. “When Derrick May and Eddie Flashin’ Fowlkes wanted to go to Chicago to see the house scene, the people they got in the car with were an older crew that went to Chessmate, a crew that had been part of that primarily gay disco community,” says Gholz.

In the ’80s, as the sexual segregation of nightlife in Detroit began to loosen up, mostly-queer venues like Heaven and Todd’s were important points of contact and mentorship between different generations of musicians. Many of Detroit’s techno legends got their start frequenting (and often sneaking into) venues where an older generation of gay, black DJs were combining disco with the new sounds of house and garage. But these encounters are almost entirely missing from the story of Detroit techno. Gholz points out that these venues and their social networks remained mostly “off the grid.” Indeed, most of the material for this section is based on oral histories collected by Gholz; almost none of it exists in print.

And Detroit’s LGBTQ-history didn’t end in the ’80s, either. This older generation of primarily gay DJs continued to play at local parties well into the early 2000s—although most of them have either retired or passed on by now. A younger generation of queer-of-color dancers, producers, DJs, event promoters, label managers and venue staff have also come up in the scene, such as Curtis Lipscomb and Adriel Thornton. Lipscomb runs Kick, stemming from a magazine running since 1994, which organizes programs and events serving the Detroit LGBT community; Lipscomb also had a hand in founding the annual Hotter Than July festival, “the nation’s third oldest celebration of African American lesbian, gay, bi and transgender culture.” Thornton is a local promoter of both electronic music and queer culture, founding the Fresh Media Group and engaging in community activism with Detroit’s Allied Media Projects.

Acid house and rave /

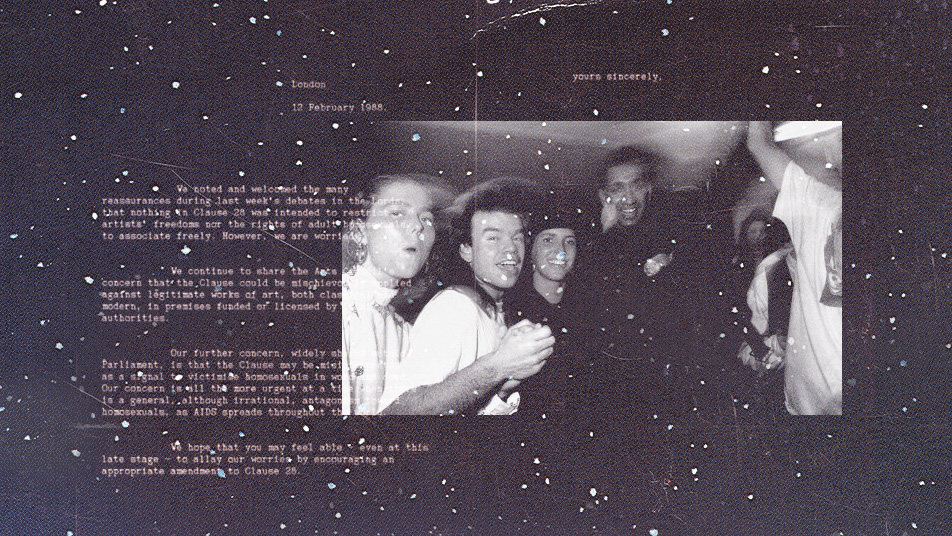

Neither of these clubs explicitly catered to a gay clientele, although both were described as open or gay-friendly. In fact, Sarah Thornton claims in her book Club Cultures: Music, Media, and Subcultural Capital, that the segregation of gay and straight nightlife was especially sharp between 1988 and 1992, when the AIDS crisis was at its peak and anti-gay legislation was being passed by the conservative government (such as Section 28 of the Local Government Act of 1988, which bears a close resemblance to Russia’s anti-gay legislation of 2013)

Things were almost too successful for Shoom and Trip, and both venues soon found themselves on the wrong side of London’s authorities. In order to avoid police pressure, many promoters began organizing underground events in warehouses and other out-of-town locations. This would form the basis of the Second Summer Of Love, the period starting in 1988 when the UK’s rave scene blossomed and soon went international. And, much like the first Summer Of Love, rave culture touted “love” and “freedom” as core values, but tended to leave traditional gender roles and sexualities undisturbed. Although rooted in queer, black and Latino nightlife—and while certainly different from “mainstream” club culture at the time—rave in the UK at the end of the ’80s had become a primarily straight, white, middle- and working-class affair.

By the beginning of the ’90s, the first rave events were being organized in New York (Storm Rave) and Toronto (Exodus). With Chicago house’s sudden success in Europe, the city’s first generation of house DJs were constantly busy with overseas bookings, and so a younger generation of Chi-town DJs carried the torch into the Midwest rave scene.

But the divisions that had developed in the UK’s acid house scene also carried over into North America: by the time electronic dance music became a global phenomenon, rave events were attracting a crowd that was mostly young, white, middle class, suburban and predominantly straight. In Mireille Silcott’s Rave America, Tommie Sunshine, a well-known personality in the early Chicago rave scene, admitted that, “The way I found out about house—I think the way most white kids in Chicago found out about it—was by reading about what was going on in our city in the British [magazines] Melody Maker and NME.”

There’s something ironic about Chicago’s mostly-white and heterosexual raver community finding out about their own city’s queer, black musical heritage through a magazine printed on the other side of the Atlantic. But it’s also not entirely surprising: Chicago’s urban landscape has been racially divided for decades, and it still divides its music scenes. That said, there were some points of overlap between the original Chicago house scene and the newer rave scene during the ’90s, such as the weekly Boom Boom Room party or the all-ages club Medusa’s. More recently Smart Bar, Chicago’s longest-running dance music club, has inaugurated a gay night (Queen!) and a classics-oriented, vinyl-only night (Hugo Ball), both of which have been attracting crowds from different generations, sexualities and ethnicities.