28 Jan Interview with Colby Keller

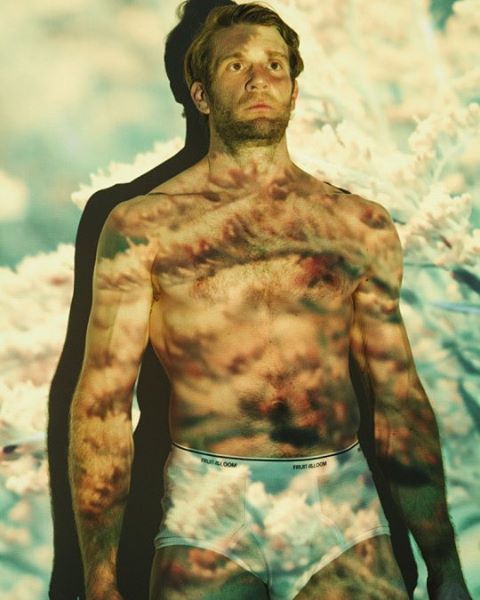

Late last year I did an interview with the one and only Colby Keller for a forthcoming new magazine called PHILE where it’s to accompany his photoshoot. And here’s the draft:

The collective body of Colby Keller

Colby Keller requires little introduction for those acquainted with contemporary gay male porn. Since his debut with Sean Cody in 2004, Keller has become a key performer whose versatile star image spans from hardcore porn to fashion modeling and collaborative art projects, such as Colby Does America, which has been realized through crowd funding and edited on collective, volunteer basis.

During these dozen years, the porn industry has gone through major economical and technological transformations fuelled by video aggregator sites, P2P sharing, amateur porn distribution and the end of the DVD era. Sean Cody itself was bought up by Men.com, which again was bought up by Mindgeek, the company running the majority of aggregator sites. This centralization is unprecedented and there isn’t much transparency to how the business as a whole operates. In what sense is the contemporary porn industry an industry?

CK: I actually feel the industrialization of porn more now than when I started. There are these monopolies that are forming. There’s more consolidation: many companies have disappeared, fallen off the map, or been bought up.

The way that Mindgeek works with Men.com is that they have a team of producers and the producer gets a deal, a certain amount of money, and they are responsible for finding models and budgeting it. That’s how they typically work, which is very different than a lot of the older companies. But there isn’t a lot of transparency to it and even negotiating pay can be very stressful.

The old model was, here’s a new guy and we use him for five or six scenes, or maybe we sign him exclusively for ten and then he’s done. In that old system, which I caught the very end tail of when I started and which was beginning to disappear largely due to online stuff, they would sign you for an exclusive, you might get paid slightly more money every video that you made, and they would be in charge of your image. They would own your image and your name and their job was to promote you. But after that exclusive period, the models have been kind of on their own. The studio might help to set up a website or something for models they like or they make a lot of money from but the models still have a lot of personal responsibility to manage their own image. And of course that’s going to be the case since the companies are there to make money. In the end of the day it’s capitalism and anyway the company can have the performers perform free labour, they’re going to have them do.

How does a self-identified communist with an education in fine art and anthropology manage his labor and porn persona in all this?

CK: All the horrible stories you can imagine in a porn company, I’ve experienced. But I also used to work at Neiman Marcus doing their visual displays for two years, 70 hours a week. I got paid minimum wages because I was a temporary worker, they didn’t want to pay my healthcare and I was really a slave to everyone else. I worked as a news cameraman too for a company that contracted with every major news outlet, and they paid me ten dollars per hour. Those experiences were a lot more traumatic and I got treated a lot worse than I probably have in the most of my porn encounters.

There is a politics of having a profession and certain things you can talk about and certain things you can’t. And you talk in a certain way particularly when that business is about selling you as this sex object. I’m in the business of turning people on and part of that should be about embracing who that person is and all the complex ways in which we people exist in the world. And that’s what desire is: it’s a complicated thing, not just a flat image that you can access for twenty seconds and then disappear and walk away from it. So I try to be as transparent as I can and I think that’s an ethical duty that I have.

That’s where politics for me enters into this. I’m not resistant to talking about problems I’ve encountered in porn, or the experiences I’ve had because it’s important for people consuming this product to know what it is. I try not to produce propaganda for the industry, or propaganda for myself.

From your perspective, what makes a good porn scene? What is a job well done for you as a professional and what are you looking for in a scene in the porn that you watch?

CK: A good scene is where we have really good chemistry and which is done really quickly: everything goes smoothly, everybody has hard-ons, we come right away and get out of there. I mean, it’s a job. I’m paid by scene and the shorter the hard day is, the better.

So that’s one kind of a good scene. Hopefully it will translate into something that an audience might appreciate but that aspect I really have no control over. It’s weird: sometimes scenes I thought were really awful turn out to be really popular, and scenes I thought were really amazing nobody pays attention to. I’ve always been curious about why that happens and when that happens. That’s another type of a good scene, one that the audience decides.

I prefer bareback porn and like scenes where there was a lot of intensity and energy and connection between people. Have to love a good internal cumshot! With Colby Does America, I tried not to qualify anything as good or bad. That always wasn’t possible because I had bad experiences with people or sex wouldn’t happen, or it didn’t happen in a way that I wanted it to happen. I found myself really loving it if there was good sex, I got good angles and images of everything and I was thinking about it as a typical porn scene. I felt confident in the content I was able to deliver when I had that secured in the bag.

There were a lot of cases where people agreed to film but we’d just end up having a conversation about sex: in one case it got to a big argument. I tried to limit that since I knew it provided a problem for those who volunteered to edit: they’re not going to want to sit and watch a 60-minute conversation. I tend to be visually oriented and think about aesthetics, so being able to set up a shot and have sex and evaluate that content was interesting for me personally, but I tried not to make a value judgment.

You’ve earlier talked about Colby Keller as a collective body of sorts, one encompassing fans and their participation as this sort of an embodied, living brand. What kind of an identity position is then Colby Keller?

CK: I used to think there was more of a pronounced separation between Colby Keller the porn performer and me who is not, and I feel less of a distance now. As my career gets bigger the two become necessarily less separated from one another.

Colby Keller is definitely a collective person and there are a lot of people who shape that. Some aspects of that person I have nothing to do with. There’s a way in which we perceive ourselves as these individuals that’s more mythological than it is factual – not in just biological terms and all the other organisms that contribute to our body mass – but also in the way we’re socially conceived, and replicate. This mythology serves a certain purpose but it’s not one that benefits human beings and it’s definitely putting us in the position globally that’s detrimental to our success in the long term as a species.

I am a collective person, like I think everyone is and we need to start thinking ourselves more in that respect. That doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t advocate for privacy or the agency of individual organisms but we need to think in a broader sense about how we conceive of ourselves, and there is no other place to start that kind of a project than with oneself. So I think Colby, which is an extension of myself, is one way in which I can do that.

It’s difficult because I get recognition and obviously it’s my personal voice and body that’s the one doing the talking, and I’m privileged that way. If there’s something positive that comes out from what Colby Keller does, I’m usually the one who benefits from that. I try to share as much as I can with the other people who are part of this project, but that’s an interesting ethical problem. And these other people aren’t getting any monetary rewards from what we’re doing – well, rarely am I.

But I try not to dwell on the things about living a life that make me think as this myopic little, individual organism, and I try to think of myself in a more expansive sense since it’s helpful. It’s helpful to aid others in that process too, and working collaboratively is a way to manage that for each other.

This collective sense of self is something of an assemblage obviously detached from notions of individual identities as clearly bound and separable from one another. It also pushes us to think about sexual identity as this contingent thing. While sexual identities are routinely defined through binary, mutually exclusive and seemingly coherent categories – such as gay vs. straight – they keep on taking new twists and turns as we live, encounter people, places, desires and palates. In most instances, what or who one prefers at the age of 20 is a different thing that what one goes for three decades later. To what degree is sexual identity a productive concept to think and live with?

CK: It’s really a question of how we think about history. We definitely should give ourselves as much permission as possible to conceive of new ways of thinking of ourselves as sexual beings, and as beings in general. We’re always doing that, it’s probably the only thing that makes us human: we create a lot of culture that radically shapes our environment. Sometimes we do that more successfully than other times.

But in order to do that we really have to have some kind of appreciation for history and where we come from and how we got to those points. That would mean full appreciation of what those categories might entail, however they’re practiced or validated, and an understanding of them. That’s inevitably how we operate, along with a good deal of obfuscation from certain parts of our community. People benefit from certain things staying the same and they’ll try as hard as they can to prevent that process from working itself out – even though it usually does in some way.