04 Feb This Art Exhibition Unearths Punk’s LGBTQ+ Roots

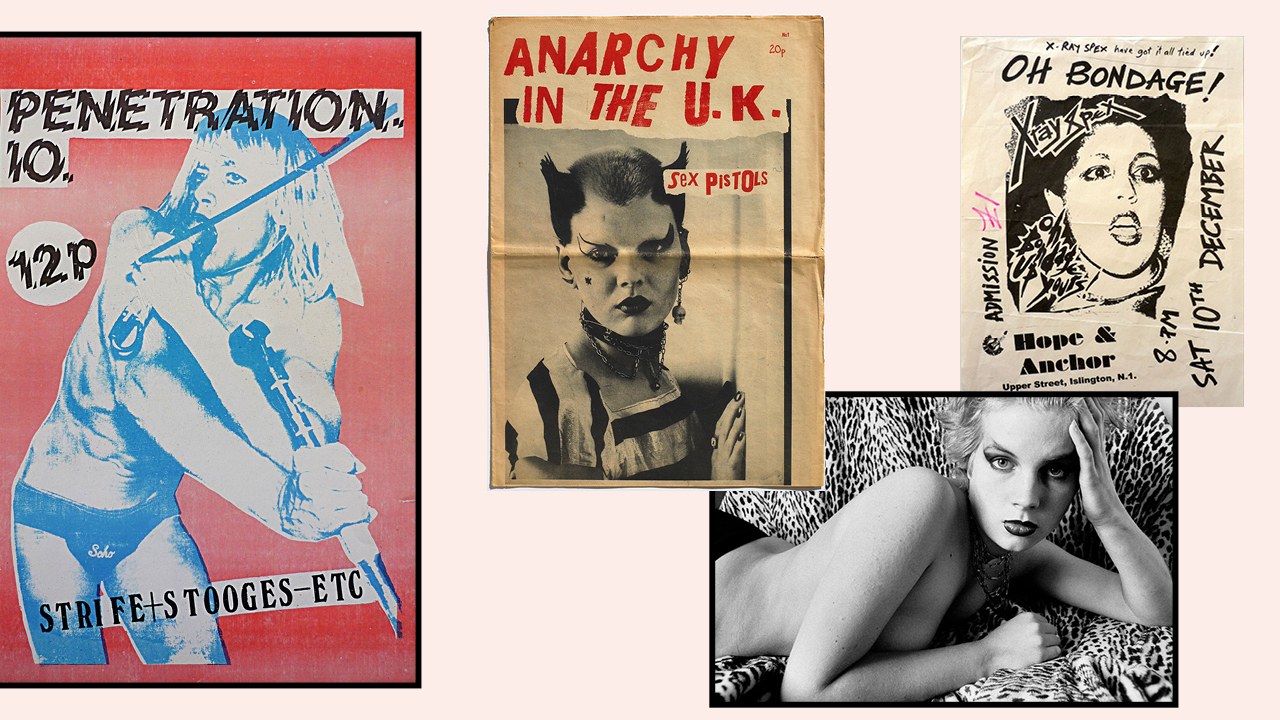

Punk Lust: Raw Provocation 1971-1985″ explores the intersection of sexuality and punk music. More of it was queer than you might think.

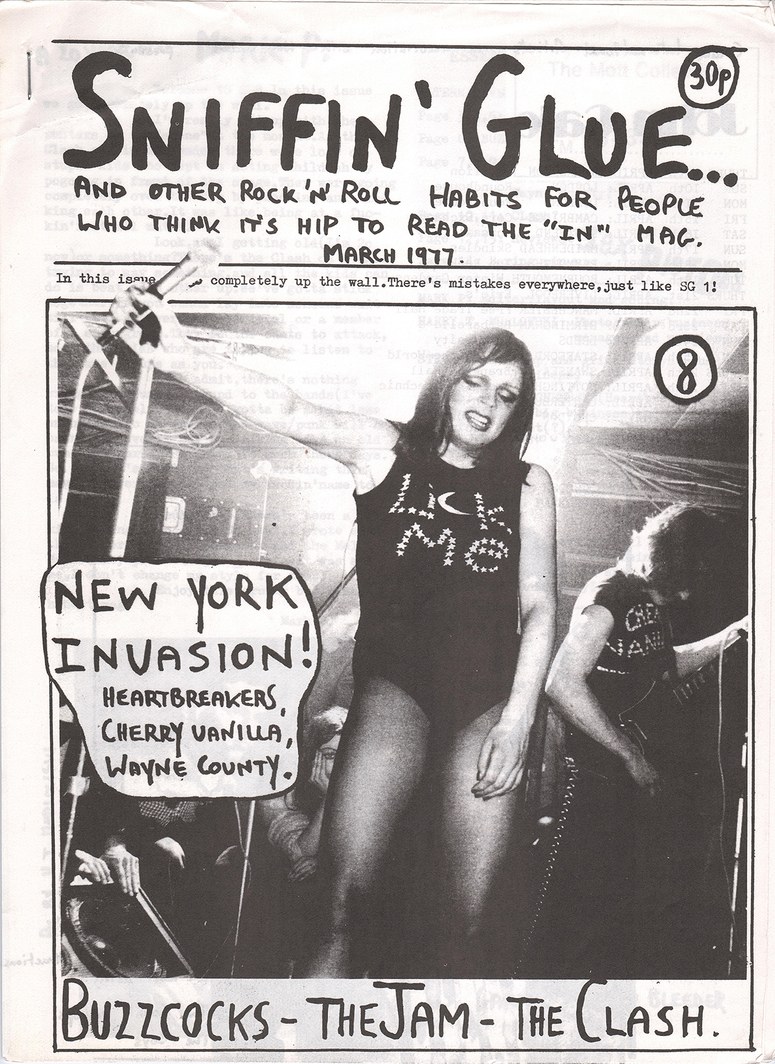

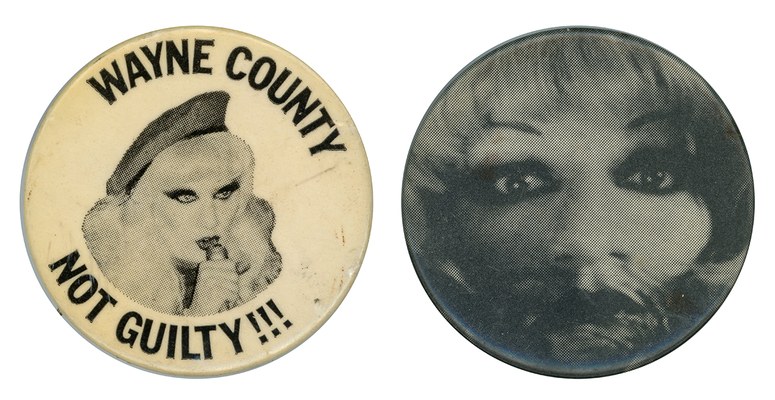

You’d be forgiven if the the word “punk” makes you picture an angry, skinny, hetero-masculine white boy, like the Sex Pistols’ Sid Vicious or the Ramones’ Joey Ramone. But while “punk” and “queerness” seem like contradictions, punk was (and is) very much queer: Whether it’s Tom Robinson Band proudly declaring they’re “Glad To Be Gay,” The Buzzcocks’ bisexual singer Pete Shelley asking if you have “Ever Fallen In Love (With Someone You Shouldn’t’ve?)” or trans pioneer Jayne County asking if her audience is “Man Enough To Be A Woman,” punk music has long engaged with sexuality and gender as a means of rejecting repressive social norms.

Punk Lust: Raw Provocation, 1971-1985, an exhibition now showing at New York City’s Museum of Sex,introduces these and other overlooked LGBTQ+ punk icons to a new generation. Curated by cultural critic Carlo McCormick, writer and musician Vivien Goldman, and artist and Museum of Sex curator Lissa Rivera, the sprawling show features over 300 objects, including seldom-seen photographs, treasured items from personal collections, such as Johnny Thunders’ leather jacket owned by Manic Panic’s Tish and Snooky, and visual art by queer artists, like David Wojnarowicz, who influenced and were influenced by punk musicians. The exhibition explores everything from punk’s intersection with the sex industry, gay leather culture’s influence on punk fashion, the deep impact of queer culture on punk’s roots, and more. More than sheer shock value, Punk/Lust asserts that punk’s transgressive aesthetics were a radical and rebellious political critique of heteronormativity, which continues to resonate today.

them. spoke with curator Lissa Rivera on the inspiration behind Punk Lust, the difference between punk and disco’s engagement with sexuality, and if she found any resistance to revealing punk’s queer influences.

What initially inspired you to organize Punk Lust?

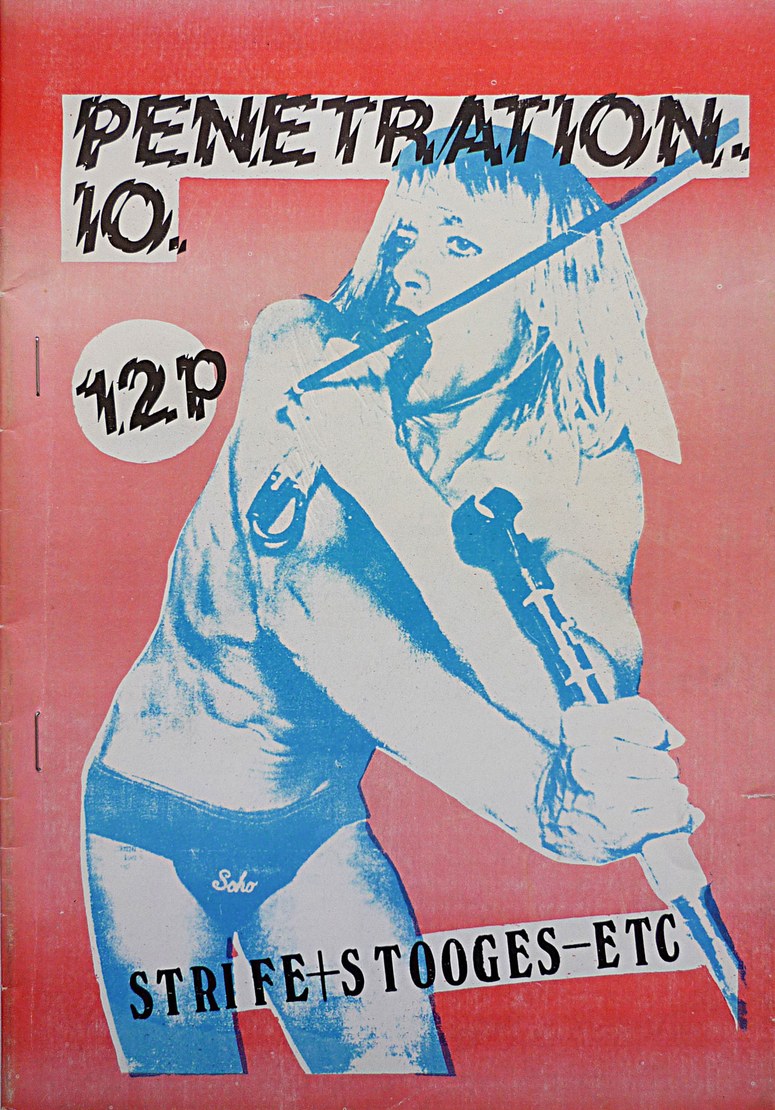

The exhibition started with Toby Mott’s collection [of punk memorabilia] and his book called Showboat:Punk/Sex/Bodies. For me, I was looking forward to doing this show because punk is such a part of my identity. I grew up with punk. My dad identified as a punk in the 70s and taught me everything about life through his record collection. It was also good to work with both Vivien Goldman and Carlo McCormick. Vivien was part of the band The Flying Lizards, did her own independent music, and worked with Sounds magazine back in the day. And Carlo knows everyone from New York. So they were able to call people on the phone that they hadn’t talked to in years for the show. The show is really personal for everyone. What was really great is that I was able to trace everything back to queer culture in a way that I don’t feel is done very often.

The exhibition begins with punk’s influences, many of which are queer, like John Waters, Divine, Candy Darling, and others in Warhol’s milieu. What was the influence of queer culture on punk?

I wanted to be able to connect everything back to Andy Warhol and David Bowie. If you read all the history, especially of British punk, they all worshipped Bowie and androgyny in general. Similarly, Warhol did exciting things with the Velvet Underground and their intersection with the queer and trans community in the 1960s, with songs like “Venus in Furs” or “Candy Says.” It would be completely revelatory to any young person that listened to them. Another person who often gets lost in this history is Jayne County, who was roommates with Holly Woodlawn and Jackie Curtis, and was also a part of the Stonewall riots.

It was also interesting to see who Malcolm McLaren was looking at. He was looking at Kenneth Anger’s Scorpio Rising and leather culture. There’s more of an intersection with gay leather culture than you would normally assume.

I’m glad you mentioned Jayne County, who emerges as a significant figure in the show.

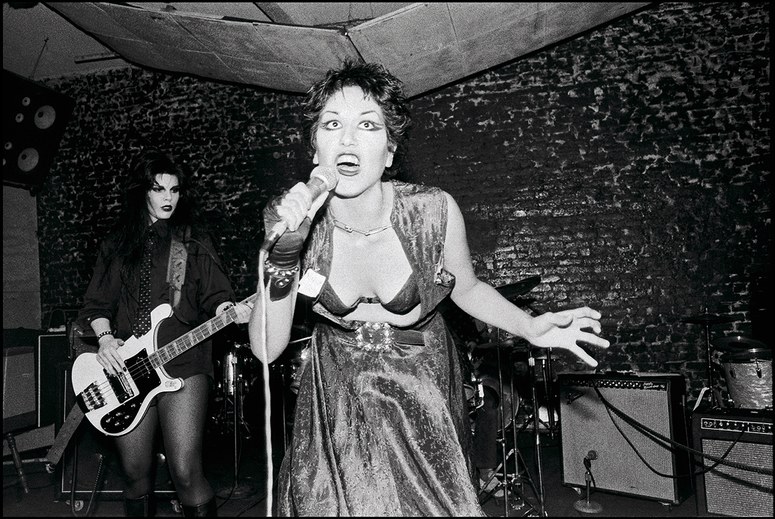

It was almost unanimous that all the collections coming our way had a ton of material related to Jayne, as well as Debbie Harry. They were both playing on the archetype of the blonde and destroying the Marilyn Monroe image of what femininity is. We were able to put so much of Jayne in this show, which you don’t see as often. Her band had a residency at Max’s Kansas City, when Debbie Harry was just a waitress and Patti Smith was trying to get in the door. Jayne was already busting people with microphone stands and performing with prosthetic vaginas.

LGBTQ+ culture and politics seem more typically associated with disco during the same period. With the long-standing division between disco and punk, how did their engagement with sexuality differ?

With disco, it was about an ecstatic release coming out of Stonewall. Pre-Stonewall, LGBTQ+ people were used to horrible abuse, having to be in mob-run bars and pay off the cops in order to exist. Disco came out of this opportunity to be public. It was feminine, queer, and embraced people of color. If you’re repressed for a long time and all of a sudden being celebrated, you become much more expressive and realize there’s so much more to discover about life. It was about creating a world to explore that didn’t just relate to heteronormative expectations. It was also a way to transcend the music charts, because Billboard was controlled by a few white men in a really corporate world. There weren’t many ways to break through, but in clubs, when they were spinning records, they could compete. There was immense power.

Punk was very anti-commercial; I relate it more to the sex industry. If you think about the landscape of New York City at the time, people were working in peep shows, and as professional dommes and sex workers. It wasn’t necessarily seen as taboo, but as an exciting way to explore your identity. This was a group of people who worshipped Rimbaud, Jean Genet and William S. Burroughs. There was freedom because rent was so low you could do phone sex a couple nights a week and have enough money to go out every night. And because it all worked to combat moral norms, there was a sense of excitement.

Punk looked at the hypocritical society of the 1970s, which was simultaneously a return to the restrictive morals of the 50s while Deep Throat became the highest-grossing film of 1972. Punk engaged with these conflicting ideologies and the absurdity of it all. There’s also a certain level of nihilism in punk and a desire to see how far you could push yourself. This is actually true of disco as well. There’s a desire to see how much you could experience life, whether your pleasure was risk or ecstasy.

Many prominent punk musicians played with gender, starting with the New York Dolls, who were wore makeup, platform heels and feminine clothing. How did gender fluidity evolve with punk?

The New York Dolls were directly influenced by Warhol and the Theatre of the Ridiculous, for sure. It’s really interesting because if you listen to Johnny Thunder’s solo work, he has a song called, “I’m A Boy, I’m A Girl.” I wonder what they were tapping into. In the early 1970s, there was a certain level of ambiguity that the movement evolved away from. It seemed to evolve into something that was more specifically geared toward queer offshoots of punk, like homocore or Derek Jarman’s films. There were more directly queer works that weren’t necessarily ambiguous.

You mentioned before that queerness’ influence on punk is often not shown. Did you find any resistance to finding the queer side of punk?

I didn’t really find that. It is funny, though, that when people heard we were doing a punk show about sex, they said, “No one had sex.” I had to explain that it wasn’t about your sex life per se, but about the visual language of sexuality, the use of explicit lyrics and partaking in sex work. They began to open up. Punk actually wasn’t very sexually decadent at all, which was very different from disco. There were exceptions, of course, but a lot of people mentioned it being a barren time for them, mostly because of heroin and other things.

But, to your point about queerness, with our current cultural climate being less dependent on gendered binaries, many people I talked to were able to speak more freely about their attractions or their desire to be between binaries. The literature in rock magazines at the time was very misogynistic. Now it’s much less so. I don’t feel like the show is revisionist at all. I mean, Amanda Lear was on the cover of Roxy Music’s album, who themselves were so open, sexual and free. Iggy Pop was also effeminate, and there is the later image of him in a dress. Looking at it now, there is a kind of freedom this 1970s generation is feeling. There’s not as much shame now about the spectrum of sexuality or desire.