21 Dec “Hiding the Tears in My Eyes – BOYS DON’T CRY – A Legacy”

by Jack Halberstam

Boys Don’t Cry, 1999

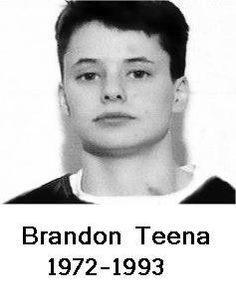

In 1999, just six years after the rape and murder of a young gender variant person, Brandon Teena, and two friends in a small town in Nebraska, Kim Peirce released her first film, a dramatic account of the incident. The film, Boys Don’t Cry, which took years to research, write, fund, cast and shoot, was released to superb reviews and went on to garner awards and praise for the lead actor, Hilary Swank, and the young director, Kim Peirce, not to mention the film’s production team led by Christine Vachon. The film was hard hitting, visually innovative and marked a massive breakthrough in the representation of gender variant bodies. While there were certainly debates about decisions that Peirce made within the film’s narrative arc (the omission of the murder of an African American friend, Philip DeVine, at the same time that Brandon was killed), Boys Don’t Cry was received by audiences at the time as a magnificent film honoring the life of a gender queer youth and bringing a sense of the jeopardy of gender variant experiences to the screen. It was also seen as a sensitive depiction of life in small town USA. Kim Peirce spoke widely about the film in public venues and explained her relationship to the subject matter of gender variance, working class life and gender based violence.

In recent screenings of the film, some accompanied by Peirce as a speaker, others just programmed as part of a class or a film series, younger audiences have taken offence to the film and have accused the filmmaker of making money off the representation of violence against trans people. This at least was the charge made against Kim Peirce when she showed up to speak alongside a special screening of the film at Reed College in Oregon, just days after the Presidential election. Unbeknownst to the organizers, student protestors had removed posters from all around campus that advertised the screening and lecture and they formed a protest group and arrived early to the cinema on the night of the screening to hang up posters.

Posters at Reed College Protesting the Screening of Boys Don’t Cry, November 2016

These posters voiced a range of responses to the film including: “You don’t fucking get it!” and “Fuck Your Transphobia!” as well as “Trans Lives Do Not Equal $$” and to cap it all, the sign hung on the podium read: “Fuck this cis white bitch”!! The protestors waited until after the film had screened at Peirce’s request and then entered the auditorium while shouting “Fuck your respectability politics” and yelling over her commentary until Peirce left the room. After establishing some ground rules for a discussion, Peirce came back into the room but the conversation again got out of hand and finally a student yelled at Peirce: “Fuck you scared bitch.” At which point the protestors filed out and Peirce left campus.

This is an astonishing set of events to reckon with for those of us who remember the events surrounding Brandon Teena’s murder, the debates in the months that followed about Brandon Teena’s identity and, later, the reception of the film. Early transgender activism was spurred into action by the murder of Brandon Teena and many activists showed up at the trial of his killers. There were lots of debates at the time about whether Brandon was “butch” or “transgender” but queer and transgender audiences were mostly satisfied with the depiction of Brandon Teena in Boys Don’t Cry. The film appealed to many audiences, queer and straight, and it continues to play around the world.

Director, Kimberly Peirce

The accounts given of these recent protests at Reed College give evidence of enormous vitriol, much of it blatantly misogynist (the repeated use of the word “bitch” for example) directed at a queer, butch film maker and they leave us with an enormous number of questions to face about representational dynamics, clashes between different historical paradigms of queer and transgender life and the expression of queer anger that, instead of being directed at murderous enemies in the mainstream of American political life, has been turned onto independent film makers within the queer and LGBT communities. Since this incident at Reed, I have heard from other students that they too felt “uncomfortable” with the representations of transgender life and death in Boys Don’t Cry. These students raise the following objections to the film some fifteen years after its release:

First, younger trans oriented audiences want to know if Peirce herself is trans. And they understand her as a non-trans person who is making money from the representation of violence against transgender bodies.

Second, they ask about the casting of a non-trans identified actor in the role of Brandon and wonder why a transgender man was not cast to play Brandon.

Third, students in particular have objected to the graphic depiction of rape in the film and feel that the scene is poorly orchestrated and the film is too mired in the pathologization and violation and punishment of transgender bodies.

These are interesting critiques and queries and worthy of conversation in their own right as well as within a clear understanding of the film’s visual grammar and representational strategies. It is not, however, a worthy activist goal to try to suppress the film, to cast it as transphobic and to target Kim Peirce herself as someone who has profited from the exploitation of transgender narratives. The film after all cost only 2 million to make and returned almost nothing to Peirce in profits.

How might we respond to these objections then in ways that do not completely dismiss the feelings of the students but that ask for different relations to protest, to the reading of complex texts and to the directing of anger about transphobic and homophobic texts onto queer cultural producers?

Here are a few thoughts:

1. We need to situate this film properly within the history of the representation of transgender characters. At the time that Peirce made this film, most films featured transgender people only as monsters, killers, sociopaths or isolated misfits.

Dressed To Kill, 1980

Few treated transgender people with even a modicum of comprehension and even fewer dealt with the transphobic environments that were part of heteronormative family life. There were very few films prior to Boys that focused upon transgender masculinity and when transgender male characters did appear in film, they were often depicted as women who passed as men for pragmatic reasons (for example The Ballad of Little Joe, 1993) or androgynous figures of whimsy (for example Orlando, 1992).

Boys Don’t Cry is literally the first film in history to build a credible story line around the credible masculinity of a credible trans-masculine figure. Period.

2. We cannot always demand a perfect match between directors, actors and the material in any given narrative. As a masculine person from a working class background who had experienced her own sexual abuse, Peirce identified strongly with the life and struggles of Brandon Teena. Peirce is not a transgender man, but is gender variant. The film she produced was sensitive to Brandon Teena’s social environment, his gender identity, his hard upbringing and his struggle to understand himself and to be understood by others. If Peirce told a story in which the transgender body was punished, she did not do so in order to participate in that punishment, she did it because that was what had actually happened to Brandon Teena and it would have been dishonest to tell the story any other way. The violence he suffered stood, at the time, as emblematic of the many forms of violence that transgender people suffered and it called upon the audiences for the film to rebuke the world in which such violence was common place.

Hilary Swank in her break through performance in Boys Don’t Cry

3. Transgender actors should play transgender roles but that is not always possible and certainly was a long shot at the time that Peirce made the film. Furthermore, it would be more effective to argue that transgender actors should not be limited to transgender roles. Peirce conducted a national search for a trans masculine actor for Boys Don’t Cry. She did screen tests with many trans identified people and she ultimately gave the role to the best actor available who was credible as a young female-bodied person passing for male. That actor was Hilary Swank, known in some circles at the time for her role in The Karate Kid and occasional appearances on Buffy the Vampire. Given the dependence of the success of the film on the acting ability of the main actor, it was vital to have a strong performer in this role and Swank was cast accordingly. Also why should a transgender actor only play a transgender role – shouldn’t we be asking cis-gendered male directors to cast transgender men and women as romantic leads, protagonists, super heroes?

4. We should not be asking for films to make detours around scenes of sexual violence instead we should be asking about what we actually mean by violence in any given context. In Boys Don’t Cry, the rape scene was brutal, hard to shoot, hard to act in and generally a difficult and emotionally draining piece of filmmaking. But it is also a deeply important part of the film and a way of representing faithfully the brutal violence that was meted out at the time to gender non-conforming bodies and it was true to the specific fate of Brandon Teena. The brutality of the rape also cuts in and out of scenes in the police station when Brandon Teena reports the rape. The police treat Brandon as a “girl” who must have been pleased by the attention from young men and they see the young men as normal, sexual subjects.

Thus, the rape scene damns the police, highlights the role of violence in the enforcement of normativity and draws the audience’s sympathies to Brandon in a way that makes transphobia morally reprehensible. When we target scenes of rape and sexual violence in independent films about historical characters and call them unwatchable, we are making it difficult to grapple with all kinds of historical material that involves systemic violence and oppression.

But, we are also limiting the meaning of “violence” to physical assault. As so many theorists have shown, violence can also appear in the form of civility, empathy, absence, indifference and non-appearance. Violence is the glue of contemporary representation – we regularly watch films in which cars are blown up (every film with a chase scene), planes are shot down (many films with Tom Cruise or James Bond in them), superheroes sweep the streets of evil taking out hundreds of people at a time (Iron Man but also Ghost Busters), tidal waves sweep through entire cities (The Fifth Wave), colonies of fish are swallowed up by marauding sharks (Finding Nemo), a female deer is shot in front of her child (Bambi), aliens land and eliminate buildings (The War of the Worlds), zombie mobs chase humans and eat them slowly (The Walking Dead) and so on. To focus solely upon sexual violence and to ignore the more general context of cinematic violence and to take complaints only to queer directors who are struggling to represent queer life rather than to straight directors ignoring queer and trans life betrays a limited vision of representational systems and ideologies and ultimately leaves those systems and their biases completely intact.

“WHO KILLED BAMBI?” SID VICIOUS

At a time of political terror, at a moment when Fascists are in highest offices in the land, when white men are ready and well positioned to mete out punishment to women, queers and undocumented laborers, we have to pick our enemies very carefully. Spending time and energy protesting the work of an extremely important queer filmmaker is not only wasteful, it is morally bankrupt and misses the true danger of our historical moment.

STEVE BANNON/DARTH VADER