11 Sep James Baldwin on Being Gay in America

The Voice commemorated the fifteenth anniversary of the Stonewall uprising with a special section exploring “The Future of Gay Life.” For the lead feature, senior editor Richard Goldstein interviewed James Baldwin about his experiences as a gay, black writer in America. At one point Goldstein notes that writing openly about homosexuality in the 1956 novel Giovanni’s Room was “enormously risky,” to which the novelist, playwright, and social commentator replied, “Yeah. The alternative was worse.… If I hadn’t written that book I would probably have had to stop writing altogether.”

Titled “Go the Way Your Blood Beats,” the entire interview, from the June 26, 1984, issue, is below.

Goldstein: Do you feel like a stranger in gay America?

Baldwin: Well, first of all I feel like a stranger in America from almost every conceivable angle except, oddly enough, as a black person. The word gay has always rubbed me the wrong way. I never understood exactly what is meant by it. I don’t want to sound distant or patronizing because I don’t really feel that. I simply feel it’s a world that has little to do with me, with where I did my growing up. I was never at home in it. Even in my early years in the Village, what I saw of that world absolutely frightened me, bewildered me. I didn’t understand the necessity of all the role playing. And in a way I still don’t.

You never thought of yourself as being gay?

No. I didn’t have a word for it. The only one I had was homosexualand that didn’t quite cover whatever it was I was beginning to feel. Even when I began to realize things about myself, began to suspect who I was and what I was likely to become, it was still very personal, absolutely personal. It was really a matter between me and God. I would have to live the life he had made me to live. I told him quite a long, long time ago there would be two of us at the Mercy Seat. He would not be asking all the questions.

When did you begin to think of yourself in those terms?

It hit me with great force while I was in the pulpit. I must have been 14. I was still a virgin. I had no idea what you were supposed to do about it. I didn’t really understand any of what I felt except I knew I loved one boy, for example. But it was private. And by time I left home, when I was 17 or 18 and still a virgin, it was like everything else in my life, a problem which I would have to resolve myself. You know, it never occurred to me to join a club. I must say I felt very, very much alone. But I was alone on so many levels and this was one more aspect of it.

So when we talk about gay life, which is so group oriented, so tribal…

And I am not that kind of person at all.

…do you feel baffled by it?

I feel remote from it. It’s a phenomenon that came along much after I was formed. In some sense, I couldn’t have afforded it. You see, I am not a member of anything. I joined the church when I was very, very young, and haven’t joined anything since, except for a brief stint in the Socialist Party. I’m a maverick, you know. But that doesn’t mean I don’t feel very strongly for my brothers and sisters.

Do you have a special feeling of responsibility toward gay people?

Toward the phenomenon we call gay, yeah. I feel special responsibility because I would have to be a kind of witness to it, you know.

You’re one of the architects of it by the act of writing about it publicly and elevating it into the realm of literature.

I made a public announcement that we’re private, if you see what I mean.

When I consider what a risk it must have been to write about homosexuality when you did…

You’re talking about Giovanni’s Room. Yeah, that was rough. But I had to do it to clarify something for myself.

What was that?

Where I was in the world. I mean, what I’m made of. Anyway, Giovanni’s Room is not really about homosexuality. It’s the vehicle through which the book moves. Go Tell It on the Mountain, for example, is not about a church and Giovanni is not really about homosexuality. It’s about what happens to you if you’re afraid to love anybody. Which is more interesting than the question of homosexuality.

But you didn’t mask the sexuality.

No.

And that decision alone must have been enormously risky.

Yeah. The alternative was worse.

What would that have been?

If I hadn’t written that book I would probably have had to stop writing altogether.

It was that serious.

It is that serious. The question of human affection, of integrity, in my case, the question of trying to become a writer, are all linked with the question of sexuality. Sexuality is only a part of it. I don’t know even if it’s the most important part. But it’s indispensable.

Did people advise you not to write the book so candidly?

I didn’t ask anybody. When I turned the book in, I was told I shouldn’t have written it. I was told to bear in mind that I was a young Negro writer with a certain audience, and I wasn’t supposed to alienate that audience. And if I published the book, it would wreck my career. They wouldn’t publish the book, they said, as a favor to me. So I took the book to England and I sold it there before I sold it here.

Do you think your unresolved sexuality motivated you, at the start, to write?

Yeah. Well, everything was unresolved. The sexual thing was only one of the things. It was for a while the most tormenting thing and it could have been the most dangerous.

How so?

Well, because it frightened me so much.

I don’t think straight people realize how frightening it is to finally admit to yourself that this going to be you forever.

It’s very frightening. But the so-called straight person is no safer than I am really. Loving anybody and being loved by anybody is a tremendous danger, a tremendous responsibility. Loving of children, raising of children. The terrors homosexuals go through in this society would not be so great if the society itself did not go through so many terrors which it doesn’t want to admit. The discovery of one’s sexual preference doesn’t have to be a trauma. It’s a trauma because it’s such a traumatized society.

Have you got any sense of what causes people to hate homosexuals?

Terror, I suppose. Terror of the flesh. After all, we’re supposed to mortify the flesh, a doctrine which has led to untold horrors. This is very biblical culture; people believe in wages of sin is death, but not the way the moral guardians of this time and place understand it.

Is there a particularly American component of homophobia?

I think Americans are terrified of feeling anything. And homophobia is simply an extreme example of the American terror that’s concerned with growing up. I never met a people more infantile in my life.

You sound like Leslie Fiedler.

I hope not. (Laughter)

Are you as apocalyptic about the prospects for sexual reconciliation as you are about racial reconciliation?

Well, they join. The sexual question and the racial question have always been entwined, you know. If Americans can mature on the level of racism, then they have to mature on the level of sexuality.

I think we would agree there’s a retrenchment going on in race relations. Do you sense that happening also in sex relations?

Yeah. There’s what we would have to call a backlash which, I’m afraid, is just beginning.

I suspect most gay people have fantasies about genocide.

Well, it’s not a fantasy exactly since the society makes its will toward you very, very clear. Especially the police, for example, or truck drivers. I know from my own experience that the macho men — truck drivers, cops, football players — these people are far more complex than they want to realize. That’s why I call them infantile. They have needs which, for them, are literally inexpressible. They don’t dare look into the mirror. And that is why they need faggots. They’ve created faggots in order to act out a sexual fantasy on the body of another man and not take any responsibility for it. Do you see what I mean? I think it’s very important for the male homosexual to recognize that he is a sexual target for other men, and that is why he is despised, and why he is called a faggot. He is called a faggot because other males need him.

Why do you think homophobia falls so often on the right of the political spectrum?

It’s a way of controlling people. Nobody really cares who goes to bed with whom, finally. I mean, the State doesn’t really care, the Church doesn’t really care. They care that you should be frightened of what you do. As long as you feel guilty about it, the State can rule over you. It’s a way of exerting control over the universe, by terrifying people.

Why don’t black ministers need to share in this rhetoric?

Perhaps because they’re more grown-up than most white ministers.

Did you ever hear antigay rhetoric in church?

Not in the church I grew up in. I’m sure that’s still true. Everyone is a child of God, according to us.

Didn’t people ever call you faggot uptown?

Of course. But there’s a difference in the way it’s used. It’s got less venom, at least in my experience. I don’t know of anyone who has ever denied his brother or his sister because they were gay. No doubt it happens. It must happen. But in the generality, a black person has got quite a lot to get through the day without getting entangled in all the American fantasies.

Do black people have the same sense of being gay as white gay people do? I mean, I feel distinct from other white people.

Well, that I think is because you are penalized, as it were, unjustly; you’re placed outside a certain safety to which you think you are born. A black gay person who is a sexual conundrum to society is already, long before the question of sexuality comes into it, menaced and marked because he’s black or she’s black. The sexual question comes after the question of color; it’s simply one more aspect of the danger in which all black people live. I think white gay people feel cheated because they were born, in principle, into a society in which they were supposed to be safe. The anomaly of their sexuality puts them in danger, unexpectedly. Their reaction seems to me in direct proportion to the sense of feeling cheated of the advantages which accrue to white people in a white society. There’s an element, it has always seemed to me, of bewilderment and complaint. Now that may sound very harsh, but the gay world as such is no more prepared to accept black people than anywhere else in society. It’s a very hermetically sealed world with very unattractive features, including racism.

Are you optimistic about the possibility of blacks and gays forging a political coalition? Do you see any special basis for empathy between us?

Yeah. Of course.

What would that be?

Well, the basis would be shared suffering, shared perceptions, shared hopes.

What perceptions do we share?

I suppose one would be the perception that love is where you find it. If you see what I mean.

(Laughter) Or where you lose it, for that matter.

Uhm-hmm.

But are gay people sensitized by the perceptions we share with blacks?

Not in my experience, no.

So I guess you’re not very hopeful then about that kind of coalition as something that could make a difference in urban politics.

It’s simply that the whole question has entered my mind another way. I know a great many white people, men and women, straight and gay, whatever, who are unlike the majority of their countrymen. On what basis we could form a collation is still an open question. The idea of basing it on sexual preference strikes me as somewhat dubious, strikes me as being less than a firm foundation. It seems to me that a coalition has to be based on the grounds of human dignity. Anyway, what connects us, speaking about the private life, is mainly unspoken.

I sometimes think gay people look to black people as healing them…

Not only gay people.

…healing their alienation.

That has to be done, first of all, by the person and then you find your company.

When I heard Jesse Jackson speak before a gay audience, I wanted him to say there wasn’t any sin, that I was forgiven.

Is that a question for you still? That question of sin?

I think it must be, on some level, even though I am not a believer.

How peculiar. I didn’t realize you thought of it as sin. Do many gay people feel that?

I don’t know. (Laughter). I guess I’m throwing something at you, which is the idea that gays look to blacks as conferring a kind of acceptance by embracing them in a coalition. I find it unavoidable to think in those terms. When I fantasize about a black mayor or a black president, I think of it being better for gay people.

Well, don’t be romantic about black people. Though I can see what you mean.

Do you think black people have a heightened capacity for tolerance, even acceptance, in its truest sense?

Well, there is a capacity in black people for experience, simply. And that capacity makes other things possible. It dictates the depth of one’s acceptance of other people. The capacity for experience is what burns out fear. Because the homophobia we’re talking about really is a kind of fear. It’s a terror of the flesh. It’s really a terror of being able to be touched.

Do you think about having children?

Not any more. It’s one thing I really regret, maybe the only regret I have. But I couldn’t have managed it then. Now it’s too late.

But you’re not disturbed by the idea of gay men being parents.

Look, men have been sleeping with men for thousands of years — and raising tribes. This is a Western sickness, it really is. It’s an artificial division. Men will be sleeping with each other when the trumpet sounds. It’s only this infantile culture which has made such a big deal of it.

So you think of homosexuality as universal?

Of course. There’s nothing in me that is not in everybody else, and nothing in everybody else that is not in me. We’re trapped in language, of course. But homosexual is not a noun. At least in my book.

What part of speech would it be?

Perhaps a verb. You see, I can only talk about my own life. I loved a few people and they loved me. It had nothing to do with these labels. Of course, the world has all kinds of words for us. But that’s the world’s problem.

Is it problematic for you, the idea of having sex with other people who are identified as gay?

Well, you see, my life has not been like that at all. The people who were my lovers were never, well, the word gay wouldn’t have meant anything to them.

That means that they moved in a straight world.

They moved in the world.

Do you think of the gay world as being a false refuge?

I think perhaps it imposes a limitation which is unnecessary. It seems to me simply a man is a man, a woman is a woman, and who they go to bed with is nobody’s business but theirs. I suppose what I am really saying is that one’s sexual preference is a private matter. I resent the interference of the State, or the Church, or any institution in my only journey to whatever it is we are journeying toward. But it has been made a public question by the institutions of this country. I can see how the gay world comes about in response to that. And to contradict myself, I suppose, or more precisely, I hope that it is easier for the transgressor to become reconciled with himself or herself than it was for many people in my generation — and it was difficult for me. It is difficult to be despised, in short. And if the so-called gay movement can cause men and women, boys and girls, to come to some kind of terms with themselves more speedily and with less pain, then that’s a very great advance. I’m not sure it can be done on that level. My own point of view, speaking out of black America, when I had to try to answer that stigma, that species of social curse, it seemed a great mistake to answer in the language of the oppressor. As long as I react to “nigger,” as long as I protest my case on evidence of assumptions held by others, I’m simply reinforcing those assumptions. As long as I complain about being oppressed, the oppressor is in consolation of knowing that I know my place, so to speak.

You will always come forward and make the statement that you’re homosexual. You will never hide it, or deny it. And yet you refuse to make a life out of it?

Yeah. That sums it up pretty well.

That strikes me as a balance some of us might want to look to, in a climate where it’s possible.

One has to make that climate for oneself.

Do you have good fantasies about the future?

I have good fantasies and bad fantasies.

What are some of the good ones?

Oh, that I am working toward the new Jerusalem. That’s true, I’m not joking. I won’t live to see it but I do believe in it. I think we’re going to be better than we are.

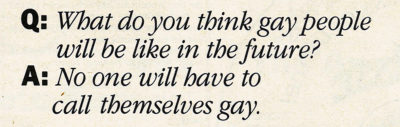

What do you think gay people will be like then?

No one will have to call themselves gay. Maybe that’s at the bottom of my impatience with the term. It answers a false argument, a false accusation.

Which is what?

Which is that you have no right to be here, that you have to prove your right to be here. I’m saying I have nothing to prove. The world also belongs to me.

What advice would you give a gay man who’s about to come out?

Coming out means to publicly say?

I guess I’m imposing these terms on you.

Yeah, they’re not my terms. But what advice can you possibly give? Best advice I ever got was an old friend mine, a black friend, who said you have to go the way your blood beats. If you don’t live the only life you have, you won’t live some other life, you won’t live any life at all. That’s the only advice you can give anybody. And it’s not advice, it’s an observation.