07 Mar Carolee Schneemann, Protean Artist Who Helped Define Contemporary Avant-Garde, Has Died at 79

Carolee Schneemann, whose venturesome works in an array of mediums forthrightly address societal taboos around sex and gender, the politics of representation, and the very nature of self-expression, has died at the age of 79. Her passing was confirmed by P.P.O.W. gallery, her representative in New York along with Galerie Lelong.

Over the course of Schneemann’s multifarious 60-year career, her art came to form the bedrock of radical traditions like performance art and body art, even while she insisted on identifying herself all the while with a traditional label. “I’m a painter,” she said in 1993. “I’m still a painter and I will die a painter. Everything that I have developed has to do with extending visual principles off the canvas.”

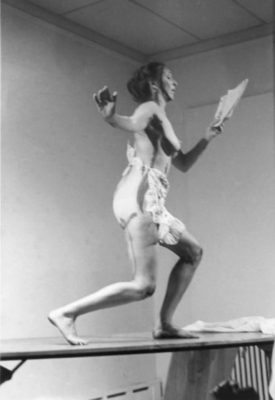

Schneemann’s corpus is so gloriously diverse that it is impossible to summarize it by naming a single defining piece, but among her most famous (and infamous) works is Meat Joy, a 1964 film of a performance featuring eight scantily clad dancers who writhe together, with animals parts soon joining the melee. It’s a bacchanalian display—unapologetic and exploding with pleasure—an utterly indelible work of art.

“Meat Joy has the character of an erotic rite: excessive, indulgent; a celebration of flesh as material: raw fish, chickens, sausages, wet paint, transparent plastic, rope, brushes, paper scrap,” Schneemann wrote. “Its propulsion is toward the ecstatic, shifting and turning between tenderness, wildness, precision, abandon—qualities that could at any moment be sensual, comic, joyous, repellent.”

Describing the work on another occasion, in terms that could very well serve as a manifesto for her entire career, she said, “The culture was starved in terms of sensuousness because sensuality was always confused with pornography. The old patriarchal morality of proper behavior and improper behavior had no threshold for the pleasures of physical contact that were not explicitly about sex but related to something more ancient—the worship of nature, worship of the body, a pleasure in sensuousness.”

But there is also her Interior Scroll (1975), a performance that involved her, in part, pulling a long, thin scroll from her vagina and proceeding to read a rejoinder to a male artist who had criticized her work. “The vagina had always been suppressed, detested, denied religiously, treated as if it was not a source of extreme pleasure and sensation and power,” told The Cut in 2016. “I’ve always been very concerned with the vitality of the vagina and that denial culturally.”

And there is Up to and Including Her Limits(1973–76), for which she strapped herself, naked, into a tree surgeon’s harness hanging from the ceiling. Stretching out to nearby walls and the floor to mark them with crayon, she reengineered the explosive, machismo-filled mark-making of Abstract-Expressionism into an activity that was physically and psychologically constricted, making art by fighting against constraints.

Schneemann was born in 1939 in Fox Chase, Pennsylvania, northeast of Philadelphia. Her father was a physician and her mother was a homemaker. “I remember looking at all of his anatomy books,” she told the artist Pipilotti Rist, of her father, in a 2017 interview. “He was happy that I would prowl around and look at things that I wasn’t supposed to see.”

Her parents did not approve of her going into art. “I was so lucky that Bard gave me a scholarship,” she told Rist. “It was a miracle.” Though college was not exactly a panacea. “It was before the era of women’s self-determination had taken off,” she said. “My teachers always said, ‘You’re very talented, but don’t set your heart on art. You’re only a girl.’ ”

Bard suspended her for painting nude self-portraits, but she went on to graduate. That forced time off proved to be fortuitous, however. Attending Columbia University, she met her future partner of 12 years, the avant-garde composer James Tenney, who would figure in another storied project, Fuses (1967), an abstracted film shot over a number of years that features the couple having sex.

After college, she went to the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, along with Tenney, to earn an MFA, then they headed to New York, which was becoming a hothouse for interdisciplinary art as experimental projects proliferated. Soon, she was playing an active role in that close-knit community and helping to form the Judson Dance Theater. (That pivotal collective was the subject of an exhibition that just closed at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.)

“We were all, you know, like blind with self-determination, that we were going to do something wonderful,” she told the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art about Judson. “And these concerts are extraordinary, with no money.”

As with so many women artists of her generation, major institutional recognition came late for Schneemann, even though she was critically lauded and admired by peers and younger artists. But such accolades did eventually come.

In 2015, the Museum der Moderne Salzburg in Austria presented a full-dress retrospective, “Kinetic Painting,” which traveled to MoMA PS1 in New York in 2017, the same year that she received the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement award from the Venice Biennale.

Schneemann’s influence is profound. Artists informed by her work, as Hilarie Sheets pointed out a few years back, include Matthew Barney, Marilyn Minter, Ragnar Kjartansson, and Lena Dunham, to which one might add Narcissister, Ana Mendieta, Rist, and just about anyone who, over the past half-century, has taken the body and identity as intricate, powerful, multivalent things—and as endless dynamos for exploration, rather than as loci for shame.

To a degree matched by very few other artists, Schneemann had an absolute allergy to resting on her laurels, and shrugged off any easily defined style over the years, as she shot videos, constructed installations, and continued to paint in various ways, often combining those different forms into single productions.

“Of course, the most important work is what I’m going to do tomorrow,” she said.

Asked by Rist about the best advice she had ever received or given, Schneemann opted to answer with the latter and said, “I guess my best advice is this: Be stubborn and persist, and trust yourself on what you love. You have to trust what you love.”