25 Apr AN ALTERNATE HISTORY OF SEXUALITY IN CLUB CULTURE: PART 4

There are many stories that come from outside of Europe and North America, but Lerato Khati’s perspective from South Africa’s largest city can give some insight into how queer dance scenes developed there. Khati manages Uzuri Recordings and Uzuri Artist Bookings & Management, which includes artists like Portable, Tevo Howard, DJ Qu and Levon Vincent in its roster. She also co-manages the label Süd Electronic alongside Tama Sumo and Portable/Bodycode.

Khati grew up in Soweto, a cluster of black townships that were incorporated into Johannesburg in 2002. From the late ’80s, she remembers having access to Chicago house music, mostly through tapes that were brought back from cousins and friends studying abroad in the USA. Television was also an important source of new music at the time. “I remember seeing Darryl Pandy’s ‘Love Can’t Turn Around’ video and being extremely fascinated by this larger-than-life individual,” she says. “The same went for Sylvester.”

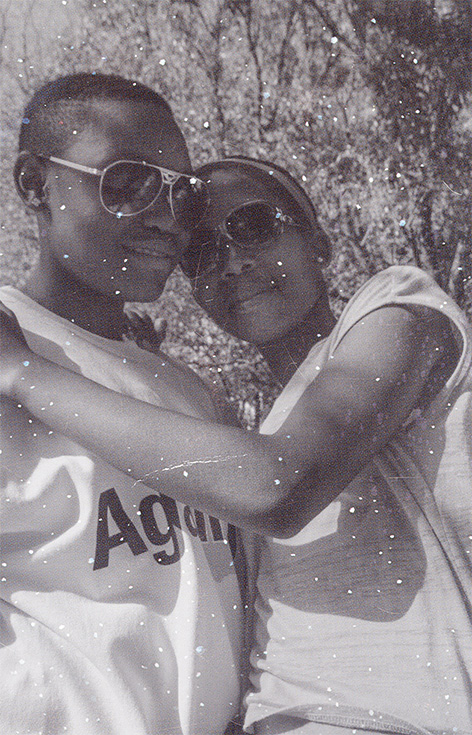

Lerato Khati

Lerato KhatiIn 1990, she attended her first rave, at an old disused cinema in the district of Yeoville, recalling it as, “a religious experience [that] would profoundly change my life.” Before the age of 20, she founded Planet Hendon, a club in a space above a coffee shop where she worked. “We had a long tradition of black women running drinking holes—called shebeens,” says Khati, “and the women that ran these illegal boozers were known as The Shebeen Queens.” In a way, she was continuing a family tradition by running a club, since her grandmother ran a jazz shebeen in the 1950s.

Being queer wasn’t easy during the ’80s and ’90s—especially in the townships surrounding Johannesburg. “It was pretty much a no-go to declare that you were anything other than heterosexual. There were terribly violent consequences for anyone that came off as even mildly camp.” The main queer-friendly house clubs during the ’90s were in the more affluent white districts, such as 4th World, Johannesburg’s first dedicated house club, Embassy Club and Idols.

Although dance music scenes in cities all over the world struggled with racial divisions, the legacy of Apartheid was particularly palpable in Johannesburg. Khati ran with a multicultural group of white, Indian, Chinese and black South Africans, but they were a somewhat exceptional crew. “We were referred to as the United Colours of Benetton at the time by a lot of folks.” But a turning point for black queers came when Brenda Fassie, the “Queen Of Kwaito” came out as bisexual. “This was a pivotal moment for a lot of Black queers,” says Khati. “You started seeing a lot more visible queers in the downtown Johannesburg area. Every Friday, people would hook up at a bar in the shopping mall there.” But there was still a need for some protection and secrecy: the password to get into the bar was abangani, the Zulu word for “friends.”

Things have changed a lot in Johannesburg since the ’90s. Khati returned to the city in 2012 and found that most of the clubs she knew had disappeared: “Downtown Johannesburg was like a ghost town.” On the upside, however, she noted a lot more visibility of gay men on the streets of the city. “Young, pretty and very fashionable black queers. This was great to see, although sadly there is still a lot of brutal violence against black lesbians, which I believe to be connected to patriarchy.”

A Club Called Rhonda in Los Angeles /

Their friendship-partnership symbolizes the mission of ACCR: Alexander is gay and Granic is straight, and they strive to bring both scenes together at their events. “When we first started, the LA scene was more segregated,” explains Alexander. “There were all kinds of social stigmas or barriers keeping people from hanging out with each other.” He also felt a deep dissatisfaction with what had become of the mainstream gay dance scene: “We always bristled at the thought of the gay community being a dumping ground for mainstream pop rehashes.”

Both of them felt there was a need in LA for what Granic calls, “a safe place for the deviants, a place where gay and straight nightlife wasn’t so compartmentalized but instead encouraged to mingle.” For Alexander, ACCR is neither a gay club nor a straight club nor even a bisexual club, but rather, “all that and more; it’s a place where you can go to shed those labels and break down those walls in the interest of having a good time.” There’s a real effort to make a mess of neat sexual identities and create something more fluid. “Everybody is an opportunity,” Alexander says.

This isn’t to say that there weren’t challenges in creating an event where partygoers can feel comfortable playing with their sexual identities. “We’ve had to deal with some issues regarding gender and sexuality in the club before,” says Alexander. “When you go into a new venue and start working with a new security team, there always has to be a very clear conversation about the fact that anything goes. There is no dress code, no judgment and absolutely no violence allowed.” Another issue they sometimes deal with is a “cultureshock” that some newcomers experience when attending ACCR for the first time. “Which is a great thing to me,” Granic points out, “but some people aren’t prepared to experience all the activities happening throughout the club while listening to their favorite musician or DJ.”

And much more /

We could revisit Toronto’s dance music history and track the waxing and waning of queer involvement, from the early Church Street discos and ’90s-era warehouse raves to the legendary (and very mixed) Industry nightclub, the infamously poppers-soaked Barn, the everything-else-soaked Comfort Zone, and many other messy after-hours spaces.

We could say a lot more about San Francisco’s disco and post-disco developments, and its international profile as a city with one of the highest concentrations of prominent female DJs (see Rebekah Farrugia’s Beyond The Dancefloor).

There’s certainly a lot to say about Berlin’s electronic music scene, which is a mess of overlapping party circuits that bring together gay men, lesbians, transpeople, ethnic queers, straight folks and others—albeit rarely all in the same club.

There’s also much more to be said about ethnically-oriented events that go beyond dance music’s history of black-or-white racial politics, such the queer South Asian and Middle Eastern dance events found in many cities: Gayhane (Berlin); Jai Ho (Chicago); Besharam and Rangeela (Toronto); Urban Desi and Club Kali (London), Sholay and Color Me Queer (New York City). And we never even got to cover the vibrant “sissy bounce” scene in New Orleans, with Big Freedia, Sissy Nobby and a whole new twerking generation of queer, gender-whatever performers.

In many places around the world, the struggle for sexual equality and diversity seems to have been going backwards. Russia is the most well-known and recent example: in addition to the recent “anti-homosexuality” laws, the Promote Diversity events were organized against a backdrop of increasingly violent attacks and torture of queer people in Russia—most of which has been happening without major consequences for the attackers, which implies at least tacit approval by the authorities.

This makes things difficult for artists who have been invited to play in Russia—especially openly queer ones such as Terre Thaemlitz. “My instinct is always to be most concerned about immediate violence or retribution against local individuals. I would hate to show up, take the money and leave, then find out later that someone had to pay consequences for my actions—or simply for being associated with me.”

But this trend is certainly not limited to Russia; there are lots of places in the world where it is becoming increasingly dangerous to be gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgendered or otherwise sexually different. During her interview, for example, Lerato Khati recalled recent instances of homophobic violence in Paris, Berlin and New York City, as well as systemic violence against lesbians in South Africa. Both Jennifer Cardini and Ragnhild Nongrata reported a surprising rise in homophobia in France during the recent national debate over same-sex marriage. And last fall, India’s Supreme Court reinstated an old colonial law banning gay sex, after a lower court had overturned the law in 2009.

So it’s perhaps not so surprising that many of the DJs, producers and promoters interviewed for this article also reported sensing a decrease in sexual diversity and openness in club culture. “It is extremely sad to see clubs being less and less open these days,” says Khati. “I strongly believe that being an artist or a public figure comes with responsibility. You owe it to your supporters and audience to promote diversity and tolerance for the greater good of the world.”

And, while women continue to become more involved in the performance, production and distribution of electronic music, the whole industry remains very tough on them—especially queer women. “The sexuality of women is judged in a terrible, painful way,” says Cardini. “For example, check out the chat in the Boiler Room feed, when a lesbian or straight woman is playing.” In response to this, Tama Sumo’s appearance on Boiler Room was the occasion for a same-sex kiss-in, precisely to raise awareness around this issue. The Knutschenaktion (German for “kiss-in”) garnered a lot of positive support from the Boiler Room staff afterwards, who have been increasing their efforts to monitor the chat-room discussion as it happens in real-time.

When talk turns to bigotry, intolerance, violence and exclusion, there’s a tendency in dance music culture to take a utopian turn and imagine we will overcome these differences through the magic of music and collective partying. The belief in the power of music to overcome differences can give us a lot of comfort and hope, especially in difficult times. But Thaemlitz warns against allowing this to blind us to the problems happening here and now: “Organizing around hopes and dreams is how we get to absurdly abstract notions like ‘love is the answer,’ and that dancing or making music is enough to change the world. We end up distracted by our own mechanisms of desire, while violence and murder continues. How many trans-women have been attacked or killed in New York alone this year? How did race and poverty also play into those incidents?”

In this light, there’s more to this piece than reminding ourselves that queers were historically important for dance music, or that they’re still musically relevant now. With the ongoing mainstreaming of electronic music culture, accompanied by a worldwide conservative turn, the struggle for sexual diversity in dance music is more urgent than ever.